Making Gender Financing More Transparent

This is an online version of the report ‘Making gender financing more transparent.‘ To download the PDF version, please click here. To download the Executive Summary, please click here.

Please use the ‘SELECT LANGUAGE’ button near the top of this page to translate this content into another language.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Data capacity

Data accessibility

Data resources

Recommendations to improve gender financing data capacity - Data engagement

Coordination

Engagement by data platforms

Recommendations to improve engagement around gender financing data - Data quality

Comprehensiveness

Comparability

Timeliness

Recommendations to improve the quality of gender financing data - Conclusion

- Checklist A: Key donor recommendations

- Checklist B: Key data platform recommendations

- Acronyms

- Key terms used in this report

- Methods and sample

- Background

Figures, tables, boxes, and case studies

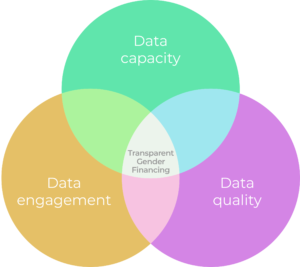

- Figure 1: Venn diagram showing three critical areas for donors and data platforms to make gender financing more transparent

- Figure 2: Levels of satisfaction among survey respondents across Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala on available financial and programmatic gender data

- Table 1: Breakdown of gender financing for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala in 2018 according to OECD CRS data

- Case study 1: Good practice in focus: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) leading in data accessibility

- Box 1: Good practice in focus: Re-balancing funding models, sustainable core funding to WROs

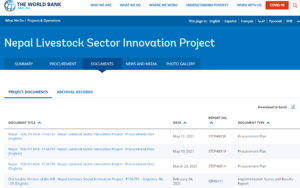

- Case study 2: Good practice in focus: The World Bank’s comprehensive gender financing data

Executive summary

There is a global consensus that addressing gender equality and empowering women and girls is a critical step in significantly improving development outcomes. Countries and donors have pledged to increase investments to address gender equality through their commitments to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5: Achieve gender equality and empower women and girls. Since the adoption of the SDGs, further global initiatives have emerged and resources have been mobilized, creating a diverse range of initiatives and funding flows targeting gender equality. As such, tracking gender financing helps to understand progress towards these global gender equality initiatives and the impact of targeted funding. Yet despite commendable efforts, it remains difficult for gender equality stakeholders to trace this funding. If it is unclear who is spending what, where, and to what effect to address gender inequality, we risk only seeing a portion of the picture.

With so much still to be done to eradicate extreme poverty and social inequality, and with the role of women and girls so central to this, we cannot afford to overlook, nor underestimate, the contribution of women and girls everywhere. Meeting the SDG targets will require transparent information, particularly at the country level, in order to direct (or redirect) funding, coordinate, and address the funding gaps, and to hold donors and governments accountable to their gender equality commitments.

This report is the final output of our Gender Financing Project that assesses the transparency of gender financing. Friends of Publish What You Fund and Publish What You Fund previously assessed the availability and quality of gender financial and programmatic information for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala. We have since conducted additional research on the availability of humanitarian, philanthropic, and Development Finance Institution (DFI) gender financing. To build on donors and data platforms’ important efforts to make information about international donors’ funded gender equality initiatives more transparent, this report presents common barriers that prevent gender equality stakeholders in all three countries from accessing high quality data. Through consultation with key gender equality donors, data platforms, and gender and data experts, this report offers actionable recommendations for donors and data platforms to address these issues at the global level.

Our report suggests that donors and data platforms can improve the transparency of gender financing by enhancing three components:

- Data capacity: The inaccessibility of data is repeatedly identified as a real barrier to better data use and to understand decision-making around the allocation of gender financing. By ensuring gender equality stakeholders’ sustained access to open, user-friendly data, and necessary data resources (funding, time, technology, and data literacy) they are more likely to collect, use, and contribute to better gender financing data and ultimately development outcomes.

- Data engagement: Publishing gender financing data is only a first step. Actively engaging with data users to understand their needs, to provide feedback loops, and to provide constructive avenues for inputs on priorities and programs will help build trust, improve use of data, and increase local ownership.

- Data quality: Although there have been advances in data quality, continued improvements in the comprehensiveness, comparability, and timeliness of gender financing data will make it more likely to be useful to—and thus used by—gender equality stakeholders. These improvements can help all relevant gender equality stakeholders’ awareness of ongoing gender equality efforts, inform program design, facilitate consultations to (re)allocate funding to effective initiatives, and ultimately to promote SDG 5 and other development outcomes.

These improvements can help all relevant gender equality stakeholders’ awareness of ongoing gender equality efforts, inform program design, facilitate consultations to (re)allocate funding to effective initiatives, and ultimately to promote SDG 5 and other development outcomes.

Key recommendations for donors and data platforms to increase data capacity, foster better engagement with data users, and improve the quality of gender financing data |

|

| International donors

(See Checklist A for all donor recommendations) |

Recommendation 1: Significantly increase the amount of multi-year, core funding for national and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), women’s rights organizations (WROs), and feminist movements to increase their data capacity. |

| Recommendation 2: Engage and share decision-making power with (potential) data users, particularly national and local NGOs, WROs, and feminist movements, in the entire data cycle of a gender equality project. | |

| Recommendation 3: Mark your funding against relevant gender markers. In particular, mark development and philanthropic funding against the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) Gender Equality Policy Marker, mark humanitarian funding against the Gender with Age Marker (GAM), and mark 2X Challenge investments accordingly. Publish assigned gender marker scores consistently to all relevant open data platforms (where applicable, alongside other gender marker scores). | |

| Data platforms

(See Checklist B for all data platform recommendations) |

Recommendation 1: Offer clear guidance for data users to access, understand, visualize, and safely publish gender financing data. Work with gender equality stakeholders to understand in which formats they would like this guidance and data (e.g., multiple languages, with metadata, in CSV/Excel formats and simplified, engaging formats such as videos, infographics, or visuals). |

| Recommendation 2: Encourage publishing organizations and your own staff to engage with local partners to share decision-making power, understand their specific gender financing data needs, reporting requirements, and capacity and resource limitations. | |

| Recommendation 3: Encourage greater consistency in the use of available gender markers by clearly linking to resources on how reporting donors can apply them to their funding and how markers compare, and by working with publishers to make underlying documentation publicly available to explain their assigned gender marker scores. | |

Introduction

By adopting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower women and girls, countries and donors have committed to increase their investments in gender equality. As a result, a growing number of global gender equality initiatives have materialized, such as Equal Measures 2030, Generation Equality Forum, Data 2X, and the Agenda for Humanity, which are helping to shine a light on the importance of open data and coordinated efforts to address the underlying causes of gender inequality. In addition to bilateral and multilateral donors’ ODA, which remains a key funding source for gender equality, resources are increasingly mobilized through DFIs and philanthropic organizations. Initiatives such as the 2X Challenge provide insight into these sources of financing. With a broad range of initiatives and a variety of funding flows targeting gender equality, tracking gender financial and programmatic data helps us understand progress towards gender equality and the impact of funding.

Despite these ongoing efforts, it is still difficult to track who is funding what, for what purpose, and with what results. Without a complete picture of the development landscape, donors and other stakeholders risk allocating their resources ineffectively and preventing greater progress towards gender equality. Meeting the SDG targets will require transparent information, particularly at the country level, in order to direct (or redirect) funding, coordinate, and address the funding gaps, and to hold donors and governments accountable to their gender equality commitments. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the importance of knowing where gender funding is going and whom it is targeting. The pandemic has not only exacerbated resource constraints and widened existing inequalities—with a disproportionate impact on women and girls, particularly marginalized women and girls—but our interviewees suggest that funding has been redirected and priorities have shifted. This Venn diagram (see Figure 1) conceptualizes our understanding of transparent gender financing and the three elements that contribute to it.

Figure 1: Venn diagram showing three critical areas for donors and data platforms to make gender financing more transparent

Note on figure 1: Venn diagram with three circles showing critical areas for international donors and platforms to make gender financing more transparent: data capacity, data engagement, and data quality.

Our research seeks to improve the publication of financial and programmatic gender equality data to promote as complete a picture of gender financing as possible and, by extension, help achieve better development outcomes. To fully understand the variety of different funding flow types, in addition to our research on bilateral and multilateral funding, we partnered with Development Gateway (DG) to investigate the extent to which we could track philanthropic and humanitarian gender financing, and independent consultant Javier Pereira (Pereira) to track the scope and impact of DFI gender equality investments.

While our Kenya, Nepal (in Nepali), and Guatemala (in Spanish) country reports cover data issues related to domestic gender financing, including the difficulty of tracking funding by women’s and feminist funds and grassroots organizations, this report exclusively focuses on funding from key international donors, specifically bilateral and multilateral donors, DFIs, humanitarian and philanthropic organizations. Since our reports discuss similar data issues, there is some overlap between the recommendations made in our country reports for national and sub-national governments and those included in this global report for international donors and data platforms.

Currently, some of these types of funding flows are being captured through the two largest sources of open aid data: OECD CRS and IATI. Both allow publishers to identify funding flows with the OECD-DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker to indicate whether an activity: has gender equality as the main objective (score 2); has gender equality as an important focus, but not as the main objective (score 1); or does not target gender equality at all (score 0). Funding that is not assigned a gender marker score is considered unscreened.

Even with this tool, development actors struggle to track current and projected gender financing, and remain unable to effectively trace how, where, and to what effect gender funds are spent. Outside of bilateral and multilateral funding, it is particularly difficult to track financing from other types of funders, such as humanitarian, philanthropic, and DFIs. While the OECD-DAC and IATI provide a starting point for tracking these financing flows, a variety of other data platforms also play a role. This report mainly focuses on the OECD and IATI data sources as many different stakeholders’ report to and use these. We will also explore the role of other major platforms and their specific issues.

Why are gender stakeholders dissatisfied with the current state of gender financing data?

Figure 2: Levels of satisfaction among survey respondents across Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala on available financial and programmatic gender data

Note on figure 2: Box graph on levels of satisfaction among survey respondents across Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala on available financial and programmatic gender data: Completely dissatisfied: 7.14%, Mostly dissatisfied: 11.90%, Somewhat dissatisfied: 45.23%, Neutral: 14.29%, Somewhat satisfied: 14.29%, Mostly satisfied: 7.14%, Completely satisfied: 0.00%

Our survey respondents across our focus countries of Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala use financial and programmatic data on gender equality initiatives for a variety of reasons, including evidence-based decision-making for programming, coordination between different stakeholder groups, monitoring and evaluation, reporting and compliance, and advocacy. Access to high quality gender financing data can therefore support these purposes. However, the majority of respondents (64%) are in some way dissatisfied with publicly available financial and programmatic gender data (see Figure 2). These respondents are mainly from national NGOs, INGOs, UN agencies, and WROs. In addition to sharing data internally and externally, these organizations are most often the users of this data. The main reasons for their dissatisfaction are insufficient data detail, inadequate gender-disaggregation, timeliness (i.e., the data is too old), incomplete location data, accessibility (i.e., data is not easily accessible), and a lack of qualitative data (e.g., key informant interviews, participatory research).

Only 21% of respondents report that they are in some way satisfied with the available financial and programmatic gender data. The majority of these respondents represent international donors or national governments who are usually the ones publishing data, particularly on globally accessible digital platforms. It is important to note that differences in opinion are often symptomatic of data publishers and users not collaborating around data and having different levels of data capacity and awareness of data sources. Engagement between, and the capacity of, publishers and users of data, or a lack thereof, are common themes running through our research findings in this report.

The next sections of the report bring together findings from our desk research, including our donor transparency assessments, key informant interviews, and surveys to explore the barriers and opportunities to more transparent gender financing data. We examine three key areas: data capacity, data engagement, and data quality (see Figure 1). While there are many components affecting the transparency of data, these three areas in particular influence the ability to access, use, and publish data. There is overlap and complementarity between these themes, but we conclude that data transparency can only be fully achieved at the juncture of all three pieces. Each data theme section closes with tailored recommendations for both donors and data platforms. For an overview of all donor recommendations, see Checklist A. To view all data platforms recommendations, see Checklist B.

Data capacity

This report defines data capacity as having the means to collect, analyze, and publish gender financing data. Individuals/organizations with sufficient data capacity are able to engage with, contribute to, and use gender financial and programmatic data.

Many interviewees, especially those from national NGOs, and community-based WROs and feminist movements, state that they currently lack the capacity to use existing open gender financing data. Similarly, some survey respondents indicate that they do not have the resource to publish their gender financing data online. The results are that current public gender financing data is unused and depicts an incomplete picture of gender financing (see the later Data quality section on the issue of Comprehensiveness).

It is important to note that the responsibility for improving gender equality stakeholders’ data capacity, especially of community-based organizations, lies with international and domestic funders. While this section will unpack the findings as they relate to international donors, our earlier country reports emphasize the responsibility of national and sub-national governments to meet their own departments’ and civil society’s data needs. Our research suggests that donors and data platforms can improve the data capacity of gender equality stakeholders, including donor country offices, by addressing what we generally perceive to be two sides of the same coin: data accessibility and data resources.

Data accessibility

Interviewees often highlight that current, openly available gender financing data is difficult to access. Ten out of the 27 survey respondents select this as a reason for their dissatisfaction with existing gender financial and programmatic data (the majority of these were from NGOs or WROs).

Our research suggests that donors and data platforms can increase gender equality stakeholders’ engagement with existing gender financing data by reducing the existing barriers to easily access this information. Barriers include monetary or time costs of accessing data, inaccessible language, and inadequate formats. Evidence to support this includes:

- A few interviewees in Kenya express that there is a high monetary and time cost to access certain government data online, especially for women at the grassroots level. Many interviewees suggest that they would be more likely to collect, use, and publish gender financing data if these activities would take less time, data bandwidth, and technical knowledge and skills.

- Our desk research and the work by DG and Pereira suggest that many data platforms do not allow development assistance to be easily filtered by gender marker scores or countries, nor do all platforms make it easy to identify a project’s total/yearly disbursements or commitments.

- Many interviewees, our analysis, and deep dives by DG and Pereira suggest that data sources are often spread out across many platforms or websites in different formats, which makes it time-consuming to find and consolidate information. For example, Pereira finds that for many DFIs you have to visit individual websites in order to find project details, and that it is often impossible to reconcile entries in the OECD CRS with those in DFIs’ own websites.

- In many cases, interviewees describe that the publication language of gender financing data is a substantial barrier (e.g., data is published in national languages rather than local or indigenous languages).

- Our international funding analysis and deep dives suggest that while some data platforms are increasingly user-friendly (see Case study 1 for an example), many require users to have significant knowledge of reporting formats and above-intermediate Excel skills to access raw reported data.

- Many interviewees would like available gender financing data to be accessible in different formats, including more simplified formats. Some interviewees, our desk research, and DG’s work suggest that available gender financing data should become more easily downloadable and interoperable (e.g., avoiding PDFs and JPGs). Other interviewees suggest donors and data platforms include abridged versions of reports with simple language, percentages and infographics, visuals/audio/video, and translation into local languages where necessary.

“There are limiting formats that make it difficult for non-technical audiences to make sense of it, such as very long reports.”—International donor, Kenya

Case study 1: Good practice in focus: The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) leading in data accessibilityUSAID has improved the accessibility of its foreign assistance data through the development of the Foreign Assistance Explorer (FAE) database. The platform collects and consolidates all foreign assistance financing across different US government agencies so data users can find the information they need in one place. The platform makes financial data available by country and year with the option to further filter by sector, implementing agency, assistance category, and region. The raw data underlying the visualizations can be downloaded in Excel. It also offers information on other donors’ funding using IATI data on the Development Cooperation Landscape Tool (found on the “Beyond USG” tab) which allows for a comparison of funding across donors reporting to IATI.

Note on graphic: Screenshot of USAID’s Foreign Assistance Explorer database homepage as an example of good practice on data accessibility. If USAID were to enable its Development Cooperation Landscape Tool to further filter funding by assigned OECD-DAC gender marker scores (which USAID reports on for their OECD CRS data but not yet for their IATI data) and link to relevant gender equality project documents, the platform would likely become an invaluable tool to gender equality stakeholders globally to access information about US gender financing. Note: By the end of FY 2021, the FAE website will be consolidated with ForeignAssistance.gov. From that point on, visit ForeignAssistance.gov for verified and complete US foreign assistance data from fiscal year 1946 to the present. |

Notably, difficulty in accessing gender financing data is sometimes caused by international donors’ seeming lack of willingness to report on their development assistance writ large. One interviewee from an NGO in Nepal mentions that India and China are reluctant to report to Nepal’s Aid Information Management System, which leads to an incomplete picture of gender financing in Nepal. These two governments similarly do not publish their development finance data to the OECD CRS or IATI. In addition, DG and Pereira’s work suggest that many humanitarian, philanthropic, and DFI funders do not report gender financial and programmatic data to various global data platforms or their own portals (see Comprehensiveness under Data quality). With important (potential) gender equality funders missing from global datasets, the remaining datasets are incomplete.

As a recent analysis by The Donor Tracker on China’s international development cooperation suggests, increasing access to such donors’ gender financing data will likely require substantial sustained advocacy efforts from both domestic and international actors. Leading reporting gender funders and data platforms play an important role to advocate for more comprehensive reporting, especially for less commonly or consistently reported funding such as DFI, humanitarian, and philanthropic gender financing.

Data resources

Throughout our research, gender equality stakeholders describe their lack of capacity to collect, analyze, and publish gender financing data as a lack of capital (i.e., funding, time, and technology) and data literacy.

Our research illustrates that insufficient data capacity is just one symptom of a larger issue of insufficient sustainable funds flowing from international donors (e.g., bilateral and multilateral organizations) to national and local organizations (e.g., NGOs, WROs, and feminist movements) to do gender equality work. The evidence to support this includes:

- Our international funding analysis (see a brief overview in Table 1) highlights that international donors’ gender financing, across our focus countries, rarely directly targets national or local NGOs. Our analysis further suggests that only 1–6% of international donors’ gender financing across our three countries supports the core functions of NGOs.

- Our interviewees state that flexible funding to gender equality stakeholders is often scarce, especially to WROs and feminist movements. Our data analysis indicates that international donors direct only between 1–2% of their gender equality funding to purpose code 15170. This code indicates whether funding supports the work of women’s rights organizations and movements, and women’s government institutions. These findings align with research conducted by the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), which finds that community-based WROs and feminist funds remain systematically under-resourced.

- Interviewees across different organization types mention that additional (core) funding for their organizations could improve their organizational (data) capacity.

“There is very little money left over from project-based funding to invest in knowledge management, so [we] struggle to share our information.” – NGO, Nepal

Table 1: Breakdown of gender financing for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala in 2018 according to OECD CRS data

Notes on graphic for Table 1: Table showing the breakdown of gender financing for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala in 2018 according to OECD CRS data. Kenya had total gender financing of USD$639 million, Nepal had USD$869 million, and Guatemala had USD$203 million. Each country has a circle representing the proportion of funding and how much (1-2%) is going to women’s rights organisations in those countries.

The table further lists the three most popular types of implementing organizations for the disbursed gender financing in each country, with #1 being the most popular. For Kenya, donor country-based NGOs, the Kenyan government, and UN agencies, funds, or commissions together implement half of international donors’ gender financing. For Nepal, the Nepali government, donor country-based private sector, and donor country-based NGOs together implement 80% of international donors’ gender financing. For Guatemala, donor country-based NGOs, donor country-based private sector, and INGOs together implement 62% of international donors’ gender financing.

Finally, the table lists the three most popular types of funded gender activities for each country. For all three countries, short-term projects are the most popular (88% for Kenya, 54% for Nepal, 89% for Guatemala). There’s a bit of variation for the second most popular type of gender finance activity. For Kenya it is basket funds managed jointly with other donors, for Nepal it is contributions to Nepal’s sector budgets and for Guatemala it is core support to various local, national or international NGOs, public-private-partnerships, foundations, and research institutes. This last type of funded activity is the third most popular for Kenya and Nepal, while for Guatemala the third most popular type of activity that receives gender financing is supporting staff from donor countries in Guatemala.

TECHNICAL NOTES

-

The numbers included in this research were the most recent and complete OECD CRS data available at the time, and were last updated in November, 2020.

-

For more information on technical language included in Table 1, such as CRS codes and definitions, please refer to the OECD’s latest DAC and CRS code lists.

-

While we agree with the OECD that the reliability of voluntary data cannot be compared to that of established bilateral ODA flows, we include all types of disbursed development assistance reported by all donors (including non-DAC members) in an attempt to offer a more inclusive picture of international donors’ gender financing.

-

It is important to note that the OECD CRS codes for core support to NGOs (Aid type B01) and to support WROs and movements, and government institutions (Purpose code 15170) include a range of recipients. When cross-referencing these codes with CRS channel codes for developing country-based NGOs (23000) or NGOs and civil society (20000), the funding numbers to national and local organizations decrease significantly.

Interviewees also mention that this lack of data capacity leads to less access to gender financing. As a result, some gender equality stakeholders experience a negative self-sustaining cycle: a lack of core funding and/or project funding for collecting/publishing data leads to insufficient data capacity, which consequently can lead to less funds to conduct gender work.

Insufficient funding, combined with the previously described time-intensive nature of finding and publishing gender financing data, results in some organizations’ inability to dedicate the necessary time or to invest in technical staff to support their data capacity.

“Data collection and sharing is time intensive and requires a lot of capacity, which isn’t necessarily available.”—INGO, Kenya

In some cases, interviewees attribute insufficient data capacity to a lack of internet technology, especially when they conduct their gender work in rural areas. As four billion people globally still lack access to the internet, increasing gender equality stakeholders’ access to gender financing data will also depend on increasing their digital access, particularly for women and girls.

Alongside monetary, time, or technological resource issues, many interviewees describe a lack of data literacy that limits their ability to engage with gender financing data. Reasons include a lack of training, skills development, or guidance to understand existing data and to safely publish gender financing data to open databases. Evidence to support this includes:

- Some interviewees indicate that they rely on the data literacy of (expensive) external experts because their organization/agency lacks in-house technical knowledge or data skills. A lack of in-house data literacy can therefore put a strain on organizations’ resources.

- In several interviews and survey responses, representatives from donor country offices express a desire to receive more data literacy knowledge or skills support from headquarters.

- Thirteen survey respondents indicate that they believe their gender financing data is too sensitive to share—these concerns are largest among organizations who aim to support the wellbeing of marginalized populations, such as LGBTQIA+ people and sex workers. This fear of sharing leads to organizations’ overly cautious approach to safeguarding data.

- Among our assessed data sources, only IATI offers data publishers and users guidance on what constitutes sensitive data and how to create exclusion policies.

“[We] lack technical knowledge and expertise to analyze data, so [we] have to hire an expert which is expensive.”—WRO and feminist organization, Nepal

To enable a better understanding of the scope of funding allocated to grassroots gender equality stakeholders, the OECD Secretariat should separate WROs from existing data categories as independent funding recipients and/or sectors.

- These findings suggest that there is a great opportunity for donors and data platforms to increase gender equality stakeholders’ access to sustained necessary resources to support their data infrastructure and literacy. Donors are encouraged to make this an explicit objective of their gender equality policy for their ODA, as is done by the Government of Canada and the Swedish government, and/or through separate feminist funds, such as the French government’s new “Support Fund for Feminist Organizations.” For more examples, please see Box 1.

Box 1: Good practice in focus: re-balancing funding models, sustainable core funding to WROs |

|

A joint report by AWID, Mama Cash, and Count Me In! Consortium highlights many examples of bilateral and multilateral sustainable funding mechanisms for feminist movements, including:

|

Based on our findings on data capacity, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommendations to improve gender financing data capacity |

|

|

Donors |

If hosting a donor portal, please also review the recommendations below. |

|

All data platforms (including the OECD CRS, IATI, donors’ own platforms, FTS, CBPF, CERF, SDGfunders, 360Giving) |

|

Data engagement

Data engagement includes a process whereby data publishers actively engage with data users. Publication is the first step. Donors should then consult with data users to understand their needs, to provide feedback loops, and to provide constructive avenues for input on priorities and programs that will help build trust, use of data, and increase local ownership.

Our findings suggest that inadequate coordination and engagement, combined with data capacity issues, limits many gender equality stakeholders’ (including government departments and feminist movements) awareness or understanding of the potential use of existing gender financing data to promote gender equality. Gender equality stakeholders tell us that without this information they cannot fully understand how international donors make funding decisions.

This can affect trust between these groups and in the longer-term could stifle the impact of donors’ and data platforms’ important efforts to make gender financing more transparent.

Coordination

A persistent issue highlighted by interviewees is the apparent lack of coordination around gender financing data between donors and implementing agencies.

Our survey findings suggest that 81% of respondents across Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala use data as a way to coordinate their activities with other national or international NGOs, donors, and governments.

As such, coordination of data is critical for development partners to inform their gender equality

work. Good coordination allows:

- involved stakeholders to understand what is happening, to fill funding or implementation gaps,

and to consult one another during the different stages of program design and implementation; - key information to flow among all concerned stakeholders in the planning and implementation of gender programs, increasing the likelihood of better outcomes.

Donors should proactively lead on the coordination role, ideally on all aspects of the project data

cycle. This will strengthen efforts to support localization. Opportunities could include:

- collaborating with implementing partners in every aspect of the data cycle: from data

collection to publication, uptake, and impact; - providing forums/spaces for in-country gender equality stakeholders to engage with funders

around their data as well as facilitating communication by publishing project contact details,

including email addresses.

There is a lack of coordination between donors’ own country offices and headquarters.

Donors’ staff at country and headquarter levels have different roles and our interviews point to a lack of coordination between the two in project design, implementation, and data collection. Country staff often find inaccuracies in information published about their programs. Headquarters staff often need more comprehensive country data. The need for better coordination also extends to having a better understanding of the country context, a problem emphasized by one NGO in Guatemala: “donors need to have a better understanding of the local context in Guatemala.” In order to analyze local contexts, find relevant gaps, make evidence-based decisions, and monitor existing programs, donors need to improve engagement between their country offices and headquarters.

Engagement by data platforms

Insufficient engagement by global data platforms around their datasets has created a lack of use among local development actors.

As highlighted earlier in this report, OECD CRS and IATI are two of the most well-known open aid data platforms globally. Both contain datasets that hold a huge amount of financial and programmatic data that is useful for designing programs and projects. Yet, our survey found a lack of use of these datasets among gender actors in our three countries.

- Sixteen out of 42 respondents across our three countries report using the IATI and/or OECD datasets;

- Of these 16 respondents, only four are from national NGOs or WROs. While the low use appears to be partly attributable to a lack of data capacity among these groups or existing issues with data quality, it also appears that it could be due to insufficient awareness and/or usefulness of these datasets.

“Very few people are aware of existing data sources and portals.” – International donor, Kenya

There is an important opportunity for donors, as well as the IATI and OECD Secretariats, to raise awareness of their datasets and to demonstrate the value of their data to address gender equality gaps at the national level. Interviewees from national NGOs and WROs state they would like to see more engagement around the use of published data and its dissemination at the grassroots level.

While our report covers aspects of humanitarian, philanthropic, and DFI gender financing data, research by DG and Pereira was limited to only desk research. This constrained their ability to look at issues of data engagement around the available data for these funding flows between gender equality stakeholders. We believe that the issues raised here likely apply to all types of international donors’ gender financing data, but further research is necessary to confirm this.

Based on our findings on data engagement, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommendations to improve engagement around gender financing data |

|

| Donors |

If hosting a donor portal, please also review the recommendations below. |

| All data platforms (including the OECD CRS, IATI, donors’ own platforms, FTS, CBPF, CERF, SDGfunders, 360Giving) |

|

Data quality

High quality information is detailed, open, timely, and comparable. Our findings suggest that currently available gender financial and programmatic data, while a product of great efforts by donors and donor platforms, is of insufficient quality to adequately support gender equality stakeholders.

Our research suggests that donors and data platforms can improve the quality of gender financing data by addressing its comprehensiveness, comparability, and timeliness.

Comprehensiveness

Our interviews, survey responses, and desk research indicate that there are significant gaps in the comprehensiveness (completeness) of available gender financing data.

Our desk research suggests that a key challenge in accessing comprehensive gender financing data lies in international donors’ insufficient marking of financing with available gender markers. Our international donor funding analysis suggests that:

- Across our three focus countries between 32–45% of all reported funding—including flows beyond ODA—for 2018 was not screened against the OECD-DAC gender marker in the CRS.

- As of July 1, 2020, an estimated 80–85% of all published IATI disbursements for our three countries was unscreened.

While members of the OECD-DAC are required to screen their ODA against the gender marker, reporting against “other” financial flows and by non-members is voluntary—though encouraged by the OECD-DAC Network on Gender Equality (GENDERNET). This means that multiple funding flows reported to the CRS and IATI, including DFI, humanitarian, and philanthropic funding, are not required to be screened against the OECD-DAC gender marker.

Several other databases allow DFI, humanitarian, and philanthropic donors to mark their funding against other gender equality markers. For instance: a couple of DFIs’ own portals include labels to clearly identify 2X Challenge funding, SDGfunders enables philanthropic funding to be marked with the label “SDG 5: Gender Equality”, and both Country-Based Pooled Funds (CBPF) and the Financial Tracking System (FTS) allow humanitarian funding to be marked with the GAM.

Despite different data platforms’ available gender markers, the deep dives done by Pereira and DG suggest that DFI, humanitarian, and philanthropic donors are unlikely to clearly mark their gender equality initiatives. Their findings include:

- Although ten out of 15 DFIs screened by Pereira report projects for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala to the OECD CRS for 2018–19, only five of them screened projects against the gender marker.

- Only four 2X Challenge members currently report to IATI, and none report gender equality projects for our three countries.

- Within Pereira’s sample, only two of the four DFIs that mention 2X Challenge projects within their own databases clearly labelled them as such. Only two private foundations funding activities in our three focus countries report to IATI.

- While DG estimates that less than a third of humanitarian funding in our three countries goes towards gender equality activities, many organizations are not using data platforms’ available gender markers. This likely translates to inaccurately low funding estimates.

Finally, several important global databases do not currently have/use gender equality markers, making the tracking of gender financial and programmatic data almost impossible. These databases include the philanthropic database 360Giving,i the humanitarian Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), and most of DFIs’ own portals.

i. 360Giving has indicated that they are currently working on including a gender marker to their database in the future.

Our research suggests that it is difficult for gender equality stakeholders to find detailed information about gender equality initiatives, especially programmatic data. Supporting evidence includes:

- The two most common issues raised in our survey are insufficient detail and gender-disaggregation of data (for both, 20 out of the 27 respondents were “dissatisfied”).

- The third most common issue was a lack of qualitative data (15 survey respondents), tied with old data (to be discussed in the Timeliness section).

- Our transparency assessment of 71 gender projects found that many of the data types valued by our interviewed gender equality stakeholders are often unavailable across our assessed platforms: less than a third of the assessed projects published clear, timely, and relevant gender-disaggregated results (31%), gender-disaggregated objectives (28%), sub-national location information (27%), project descriptions (23%), gender analyses (20%), and reviews and evaluations (14%).

- Of the assessed global data sources in our transparency analysis, and in DG and Pereira’s works, only IATI and CBPF allow organizations to systematically publish detailed results-type information, including evaluations and review documents. In some cases, FTS data will include limited results information in project descriptions.

- Within our transparency assessment sample, only the online portals hosted by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the World Bank (WB) include detailed and relevant project evaluation documents for some of their gender equality projects (see Case study 2 for an example).

- Pereira found that none of the DFIs reporting to the 2X Challenge publish results information in their portals.

Less than half of the assessed projects published meaningful information on targeted gender group(s) (42%), and fewer mentioned additional characteristics of these groups, such as their age group, race/ethnicity, disability status, social class, and religious affiliation (28%).

Without comprehensive gender programmatic data, gender equality stakeholders will experience difficulties understanding whose gender equality donors are aiming to improve, how, where within their country, and what is—or is not—working. Detailed results data, particularly in the form of evaluations and review documents, would allow development partners to learn about which gender equality initiatives show evidence of working, and thus know which initiatives should be scaled up, replicated, tailored, or avoided.

Case study 2: Good practice in focus: The World Bank’s comprehensive gender financing data

The WB International Development Association (IDA), one of the largest providers of gender funding globally, is a leader when it comes to publishing high quality gender financing data. With the WB Group’s overarching 2016–23 gender strategy’s focus on robust monitoring and evaluation, IDA provides comprehensive data on key data types frequently used by gender equality stakeholders, most notably gender analyses and gender-disaggregated results. Of the five projects assessed, three published timely gender-disaggregated results in the form of Implementation Status and Results Reports (see screenshot for example) and three published gender analyses within Project Appraisal Documents.

Note on graphic: Screenshot of the World Bank Nepal livestock sector innovation project documents list as an example of good practice on data comprehensiveness.

Comparability

Our research further indicates that there are issues with the comparability of currently available gender financial and programmatic data.

Interviewees across all three countries mentioned the lack of standardized and comparable data as a significant barrier to more transparent gender financing data. Additionally, from the 27 dissatisfied survey respondents, almost half (13) selected the inability to combine and compare different datasets as a reason for their dissatisfaction with available data on gender equality funding and projects. Our transparency assessment, DG’s findings, and Pereira’s findings further support these views.

While different data platforms are designed for different purposes, our research suggests that there are opportunities to better harmonize and complement existing gender financing data. In particular, donors and data platforms should streamline gender marker scores and, to the extent possible, data fields and terminology.

Our findings suggest that existing data does not offer reliable estimates of the scope and impact of gender financing due to inconsistent application, validation, and alignment of gender markers. Evidence to support this includes:

- Our transparency assessment finds that only two out of a sample of ten top gender equality donors across our three countries consistently report on the OECD-DAC gender marker to the CRS, IATI, and their own portal: Sida and Global Affairs Canada (GAC).ii

- Our transparency assessment underscores a previous study by Oxfam that insufficient publication of comprehensive information, such as projects’ underlying gender analyses, gender-disaggregated objectives, and detailed results, means that existing data does not allow us to validate donors’ assigned OECD-DAC gender marker scores.

- Some philanthropic, humanitarian, and donor data platforms adopt their own gender markers to indicate to what degree funded activities aim to improve gender equality. However, our transparency assessment, and the findings of DG and Pereira, suggest that these gender equality markers are often inherently different, which makes it difficult to reconcile data marked against different markers.

ii. Both Sida and GAC have developed internal datasets which link together OECD CRS and IATI data. As a result, if these donors update a project’s IATI data, it updates the corresponding OECD CRS dataset and vice versa.

“Being transparent is not just sharing information, it is sharing power.” – WRO and feminist organization, Guatemala

Greater consistency in the publication of gender marker scores across platforms would ensure that gender equality stakeholders can consistently find key pieces of information (namely, to what extent an initiative aims to improve gender equality) across different data platforms. For donors who only report on the OECD-DAC gender marker to the CRS, it would be a light lift to add the OECD gender marker scores to IATI and/or their own platforms alongside any other gender marker scores. To avoid confusion about projects’ application and alignment of gender markers, donor portals and other platforms should publish additional underlying documentation (e.g., project gender analyses, gender-disaggregated project objectives, and results documents) as to why projects are assigned each type of gender marker score, or at a minimum clearly indicate comprehensive guidance as to how different gender markers compare. Several key gender equality donors highlight that being able to access such documents would not only be useful to national or local gender equality stakeholders, but also to international donors to understand how others mark their funding.

Our research suggests that a lack of alignment between different data platforms’ data and definitions puts a stress on gender equality stakeholders’ data capacity and data literacy. Donors and data platforms can increase the comparability of data by standardizing data reporting fields and terminology and linking to related datasets on other data platforms. Supporting evidence includes:

- Several interviewees across our three focus countries, as well as our transparency assessment, DG’s reports, and Pereira’s report, propose that collecting, verifying, and publishing information is time-consuming (and expensive). Gender financial and programmatic data is often spread out and reported in non-compatible formats, making it hard to find, interpret, and contribute different pieces of information.

- Our desk research and the works by DG highlight that many platforms currently employ different definitions—or lack clear definitions on—important and often distinct terminology and filters. Examples include “gender equality”, “gender”, “humanitarian assistance”, “philanthropic funding”, and any related thematic terminology such as “gender-based violence”, “protection”, and “adolescents”. Without clear and comparable definitions, it is difficult to compare openly available financial and programmatic information on gender equality initiatives.

Efforts to streamline existing data would support in-country gender equality stakeholders’ ability to better compare and consolidate different datasets. Streamlining efforts could include standardizing existing reporting formats and terminology as much as possible (e.g., as the IATI Standard uses existing CRS definitions) and allowing donors to link to other data on the same activities reported to other platforms (e.g., as IATI allows publishers to link to external project documents and to publish other “legacy data”). It is important to note that streamlining efforts do not take-away from the original purposes of data platforms. Instead, it would be a sign that data platforms acknowledge that different datasets offer complementary information that can be useful to their own core data-users, and consequently pointing them in that direction in a clear and helpful manner.

Timeliness

Finally, our findings suggest that there is a need for donors and data platforms to increase efforts to improve the timely reporting of data and data publication processes.

Evidence includes:

- Across our three focus countries, outdated data was the third most common reason for survey respondents’ dissatisfaction with available gender financial and programmatic data.

- Interviewees indicate that current gender financing data has the potential to reflect present-day realities, but that the data is frequently too old to do this.

- Our transparency assessment suggests that donors’ evaluations and review documents published to IATI or their own portals are often more than 18 months old, without clear explanations for the publication frequency of these documents.

- Interviewees from all three countries, our desk research, and DG’s work suggest that data collection and publication procedures are insufficiently responsive to emergencies. Interviewees express that over the course of 2020, COVID-19 has both substantially affected the amount of funding towards local gender equality stakeholders’ work and the implementation of these projects. Compounded with comprehensiveness issues, our research suggests that global data platforms will not reflect such financing changes soon.

Some data platforms allow for more frequent publication of data than others. For instance, the IATI Standard encourages organizations to update their data at least quarterly, and allows for monthly or even daily updates. In comparison, gender financing data reported to the OECD CRS for a given year is at least 11 months old by the time it is validated and openly available. Since no interviewees explicitly mention IATI data and only four survey respondents use d-portal (see Table 1 in the Data engagement section), some gender equality stakeholders’ timeliness critiques might in part be addressed by increasing their awareness of platforms which publish more timely data (see Data engagement).

Donors and data platforms can meet gender equality stakeholders’ need for more timely data by making greater efforts to shorten publication timelines (carefully ensuring that the comprehensiveness and/or validation of data is not compromised), closely adopting the IATI Standard to allow for more frequent publication, or as mentioned in the previous Comparability section, by allowing publishers to link to their most up-to-date datasets. Where it is not possible to regularly report on gender equality initiatives, donors and data platforms should clearly indicate a disclaimer clarifying the reasons. Such information would improve gender equality stakeholders’ understanding of donors’ intended or achieved progress towards gender equality.

Based on our findings on data quality, we offer the following recommendations:

Recommendations to improve the quality of gender financing data |

|

| Donors |

|

| The IATI Secretariat |

|

| The OECD Secretariat and/or GENDERNET |

|

| Other data platforms (including donors’ own platforms, FTS, CBPF, CERF, SDGfunders, 360Giving) |

|

Conclusion

Understanding and being able to measure progress against global gender equality goals, such as SDG 5, is critical for delivering on commitments, holding governments and donors accountable, and creating real change to move towards global gender equality. Having quality data is fundamental to monitoring progress. Without access to quality data that clearly outlines where funding is going, to whom, to which sectors, and with what results, it is difficult for stakeholders to find gaps, plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate gender equality work.

Our desk research and interviews suggest that commendable efforts have been made by international donors and data platforms (e.g., OECD and IATI) to provide quality gender equality financing data. Despite these efforts, inconsistent labelling and publication of gender financial and programmatic data within and across data platforms means that it remains difficult for gender equality stakeholders to find, understand, compare, use, and contribute to gender financing data.

Publication of quality gender financial and programmatic data is only one piece of the puzzle. A lack of capacity among national NGOs and WROs and insufficient data engagement among stakeholders means that existing available data is not being used to its full potential. It is essential that donors pro-actively engage with their local partners to understand their gender data needs, what capacity they have to use, analyze and publish data, and support them to develop sustainable data processes of their own.

Improving gender equality stakeholders’ ability to engage with and contribute to useful and comprehensive gender financing information should benefit all gender equality stakeholders and increase the accountability of important gender equality funders’ commitments. Gender equality stakeholders play an essential role in reaching our goals for gender equality and they need to be empowered with the tools and information to enable that. By improving the quality of gender financing data, the ability to use, shape, and to fully engage with it, we improve stakeholders’ ability to make evidence-based decisions and move us closer to achieving SDG 5 and other development outcomes.

Checklist A: Key donor recommendations

| Key recommendations to donors to improve the transparency of gender financing |

Checklist |

|

| Donors (e.g., bilateral, multilateral, DFIs, humanitarian, philanthropic) |

1. Improve data capacity | |

|

||

|

||

|

||

| 2. Improve data engagement | ||

|

||

| 3. Improve data quality | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Checklist B: Key data platform recommendations

| Key recommendations to data platforms to improve the transparency of gender financing |

Checklist |

|

| 1. Improve data capacity | ||

| All data platforms (e.g., OECD CRS, IATI, donors’ own platforms, FTS, CBPF, CERF, SDGfunders, 360Giving)

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

| 2. Improve data engagement | ||

|

||

| 3. Improve data quality | ||

| The IATI Secretariat |

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

| The OECD Secretariat and/or GENDERNET |

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Other data platforms (e.g., donor portals, FTS, CBPF, CERF, SDGfunders, 360Giving) |

|

|

|

||

|

||

Acronyms

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| AIMS | Aid Information Management System |

| CBPF | Country-Based Pooled Funds |

| CERF | Central Emergency Response Funds |

| DFI | Development Finance Institution |

| DG | Development Gateway |

| FTS | Financial Tracking System |

| GAC | Global Affairs Canada |

| GAM | Gender with Age Marker |

| GENDERNET | OECD-DAC Network on Gender Equality |

| IDA | International Development Association |

| IASC | Inter-Agency Standing Committee |

| IATI | International Aid Transparency Initiative |

| INGO | International Non-Governmental Organization |

| LGBTQIA+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and/or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual and/or Ally, and all people who have non-normative gender identity or sexual orientation |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| ODA | Official Development Assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OECD CRS | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Creditor Reporting System |

| OECD-DAC | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| Sida | Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency |

| UN | United Nations |

| UN OCHA | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| USG | United States Government |

| WB | World Bank |

| WROs | Women’s Rights Organizations |

Key terms used in this report

|

Bilateral/multilateral funding |

Development assistance provided by bilateral/multilateral agencies, where the organization in question effectively controls the budget. Projects executed by multilateral organizations on behalf of donor countries are therefore classified as bilateral funding rather than multilateral funding. |

|

Data capacity |

The ability to collect, analyze, and publish data. Individuals or organizations with sufficient data capacity are able to engage with, contribute to, and use data. |

|

Data engagement |

Data engagement includes a process whereby data publishers actively engage with data users through an initiative’s data cycle. Adequate data engagement promotes trust, use of data, and increases local ownership. |

|

Data quality |

The quality of data depends on its comprehensiveness, openness, timeliness, and comparability. For data to be considered high quality and usable, it needs to meet all of these key criteria. |

|

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) |

International Financial Institutions (IFIs), bilateral and multilateral development banks which have either solely public sector investment portfolios, private sector investment portfolios, or a mix of the two. |

|

Financial data |

Information on funders’ allocations, disbursements, or commitments. |

|

Gender Equality Policy Marker |

Our report is guided by international donors’ use of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee’s (OECD-DAC) Gender Equality Policy Marker, which international donors can also report on to their International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data. International funding for gender equality can be marked as being significant (1) or the principal (2). The OECD-DAC Handbook outlines the criteria to mark aid projects/programs as having gender equality as a significant (1) or principal objective (2). |

|

Gender equality stakeholders |

Gender equality stakeholders include actors working on or directly funding gender equality initiatives. For this research, this term refers to international donors, United Nations agencies, national and sub-national government agencies, international and national non-governmental organizations, feminist and women’s funds, local women’s rights organizations and feminist movements, research institutes, and private sector organizations. |

|

Gender financing |

Disbursed or committed funding with the intention to improve gender equality, including government gender responsive budgeting and international donors’ funding. |

|

Gender financing data |

Information on gender equality initiatives’ financial and programmatic data. |

|

Humanitarian assistance |

As defined by the OECD, humanitarian assistance is the material and logistical support to “save lives, alleviate suffering, and maintain human dignity in the [immediate] aftermath of man-made crises and natural disasters.” |

|

Philanthropic funding |

Transactions from the private sector that promote economic development and the welfare of developing countries as their main objective. These transactions can originate from foundations’ own sources, notably endowment, donations from companies and individuals (including high net worth individuals and crowdfunding), legacies, income from royalties, investments, dividends, and lotteries. In general, philanthropic organizations take the form of foundations, trusts, funds, and lotteries. |

|

Programmatic data

|

Information on funders’ projects or programs. This includes basic information, such as titles, descriptions and sub-national locations, as well as more detailed performance information, such as objectives, results, and evaluations. |

Methods and sample

The findings and recommendations in this report are based on the following research elements:

- International donor funding analysis: we analyzed international donors’ gender financing data based on their self-reporting to the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) for 2018. We also conducted a transparency assessment of the availability and quality of data published by the top five highest-disbursing donors and their highest-disbursing projects for each country in 2018, leading to a sample of 71 reviewed gender equality projects. We used the OECD CRS as a starting point and compared and complemented this with information available on the International Aid Transparency Initiative’s (IATI) development portal (d-portal), relevant national Aid Information and Management Systems (AIMS), and donors’ own online project portals. For more details, please see our assessment methodology and lists of assessed gender projects and donor platforms for Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala.

- Humanitarian, philanthropic, and DFI funding deep dives: we partnered with Development Gateway (DG) to track and analyze humanitarian and philanthropic gender financing for our case study countries (Kenya, Nepal, Guatemala). For humanitarian funding, DG looked at six common funding data sources and compared the OECD-DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) GAM. For philanthropic funding, DG looked at six funding data sources used to track official development assistance (ODA). To track gender financing by DFIs, we partnered with Javier Pereira, an independent consultant. The 2X Challenge (a commitment by G7 DFIs to collectively mobilize resources alongside other DFIs to invest in women) dataset was used as a starting point to track gender equality investments, which were then compared with projects found using the OECD-DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker. For more information, please see the individual reports on humanitarian, philanthropic, and DFI gender financing data.

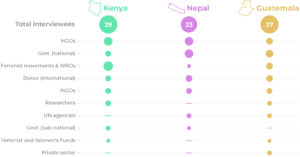

Note on graphic: Total interviews by organisation type ranked from most to least in Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala. The categories replicate what is mentioned in the text, with the most interviewees representing NGOs and the least interviewees representing the private sector.

- Interviews: we conducted 79 interviews with key stakeholders working on gender equality across our focus countries: Kenya (29), Nepal (23), and Guatemala (27). We asked them to reflect on the current gender financing landscape in their countries as well as their data priorities and to suggest transparency improvements. The interviewees work for national (14 interviewees) and sub-national governments (3), national NGOs (16), feminist movements/ WROs (13), international donor agencies (11), international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) (9), research institutes (5), United Nations (UN) agencies (4), feminist and women’s funds (2), and private sector organizations (2).

- Follow up survey: to complement our interview findings, we sent out a multiple-choice online survey to all interviewees to ask them for more disaggregated information about the types of data they use, share, and need for their gender equality work. In total, 42 interviewees (14 from Kenya, 12 from Nepal, and 16 from Guatemala) filled out the survey, including from national NGOs (14 interviewees), national government (5), sub-national government (2), feminist movement/WROs (6), international donor agencies (6), INGOs (3), UN agencies (3), and research institutes (3).

Background

WHO WE ARE

Friends of Publish What You Fund was established in May 2015 with the objective of promoting better foreign assistance outcomes by improving access to timely and relevant information, with a specific focus on the work of the United States.

Publish What You Fund is the global campaign for aid and development transparency. We envisage a world where aid and development information is transparent, available, and used for effective decision-making, public accountability, and lasting change for all citizens.

ABOUT OUR PROJECT

The goal of the Gender Financing Project is to improve the publication of financial and programmatic gender equality data to help relevant stakeholders direct (or redirect) funding, coordinate, and address funding gaps, and to hold donors and partner governments accountable to their gender equality commitments. This is expected to contribute to more effective funding of gender equality programs and, therefore, ultimately lead to better development outcomes.

We undertook case studies in three countries: Kenya, Nepal and Guatemala. For each country, we assessed the availability and quality of publicly available information, including government budgets and open data portals, collected primary data on data use, and tracked the available gender financial and programmatic data to determine how government and international funders can better meet gender equality stakeholders’ needs. We used a common methodology, combining desk research and data analysis, interviews, surveys, and consultations with top gender equality donors, to ensure a consistent approach across countries. See our methodology for more details on our country selection and research methods.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This report was researched and written by Jamie Holton and Henry Lewis, and reviewed by Alex Farley-Kiwanuka and Sally Paxton.

It was produced with financial support from Save the Children US and Plan International USA. These organizations are global advocates for gender equality and the localization of humanitarian response and development assistance. They are supporting this project in furtherance of their work, including to support frameworks such as the Grand Bargain and the Call to Action on Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies, to advance locally-led development, funding flexibility, and to strengthen financial and technical resources for women’s rights organizations and girl-led groups and networks.

The findings and recommendations in this report are built on the research conducted by our consultants Linet Juma (Kenya), Swechchha Dahal (Nepal), Gabriela Muñoz (Guatemala), Carmen Cañas and Beverley Hatcher-Mbu (Development Gateway—DG), and Javier Pereira (A&J Communication Consultants).

The report was copy edited by Liz Evers and designed by Definite.design.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for offering feedback on our research: Amanda Austin (Equal Measures 2030), Lorie Broomhall (Plan International USA), Tania Cohen (360Giving) Denmark Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tenzin Dolker (Association for Women’s Rights in Development—AWID) Katherine Duerden (360Giving), Thao Hong (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), Global Affairs Canada, Eduardo Gonzalez (Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation—AECID), Petya Kangalova (International Aid Transparency Initiative—IATI Secretariat), Anne-Marie Levesque (FinDev Canada), Sarah McDuff (IATI Secretariat), David Megginson (Centre for Humanitarian Data, UN OCHA), Save the Children US (staff at HQ and country offices in Kenya, Nepal and Guatemala) Agnes Surry (Asian Development Bank), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Jessica Espinoza Trujano (2X Challenge), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Lola Martín Villalba (AECID)