News roundup – Are donors matching local funding pledges with action, plus the need for better MDB mobilisation data

Welcome to the latest roundup of news from the world of aid and development transparency.

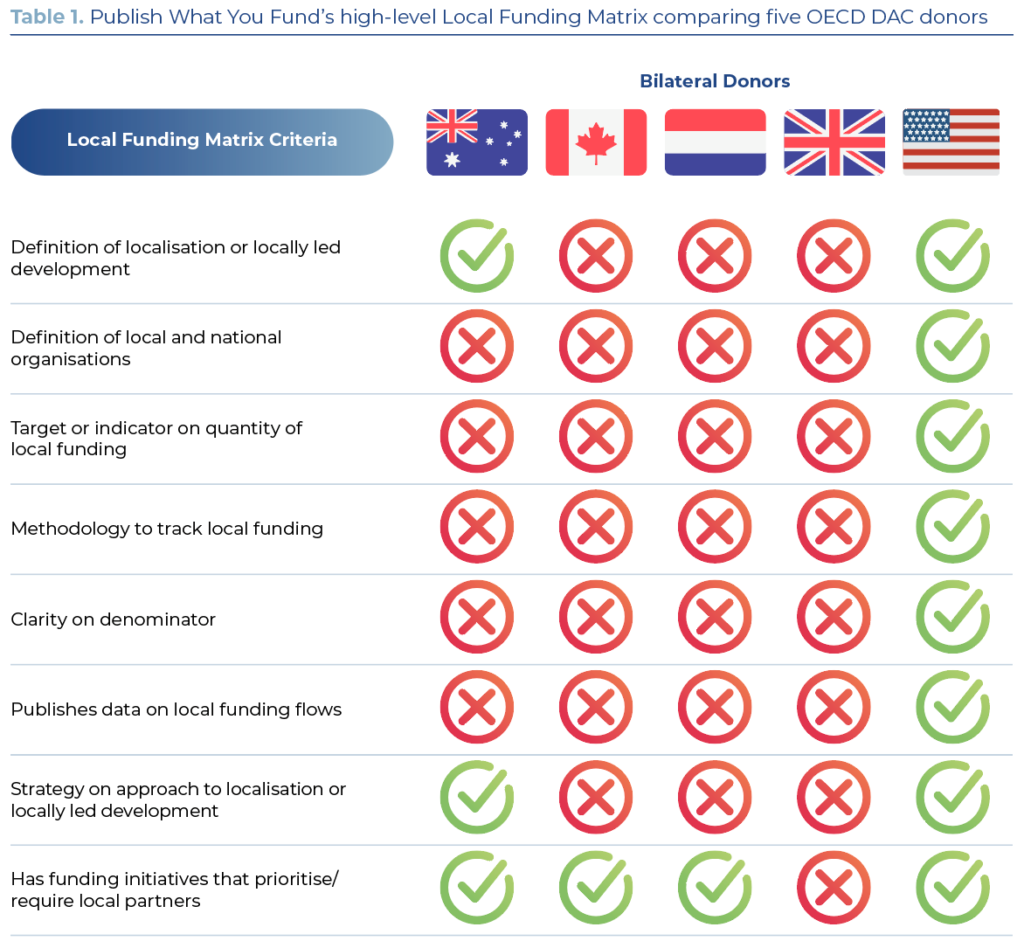

Most donors are not matching their local funding pledges with action on tracking and reporting

Many bilateral donors have signed up to international agreements to take a more locally led approach and transfer a greater share of resources to local partners. But our new study finds that many of the same donors are not sharing any practical evidence of increased local funding. Commitments Without Accountability, the new Publish What You Fund report, highlights that four out of five donors do not have localisation strategies or clear definitions, targets, or methods for measuring progress in funding shifts. Without transparent measurement and reporting, stakeholders cannot determine if localisation commitments are being fulfilled or hold donors accountable.

Of the donors included in the study, the United States Agency for International Development stands out as the only donor with a comprehensive target and public data measuring its progress toward local funding goals. While it is far from achieving its target to allocate 25% of direct funding to local partners by 2025, its structured approach can offer valuable lessons for other donors on tracking local funding. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has made some progress by developing dedicated documentation on locally led development which includes a definition and measurement indicators. The other donors in the study – Global Affairs Canada, the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) – have made slower progress on localisation.

All now have the opportunity to ensure their evolving strategies and systems support locally led development. Only then will we have the evidence to know if donor promises on localisation have been fulfilled.

This work builds on our Metrics Matter series, and we’ll be discussing the findings in more detail at an event in January – more details to follow soon.

Watch now – What we don’t know can hurt us: Better measurement and disclosure of MDB private finance mobilisation data

The need for greater multilateral development bank (MDB) mobilisation of private finance remains a hot topic. But we lack sufficient evidence on current performance to assess where the best opportunities for mobilisation lie—including by sector, country, region, and financial instrument. In October, we completed our ambitious work program aimed at strengthening mobilisation measurement and reporting and launched a well-evidenced set of recommendations on what needs to be measured and disclosed to be most useful to public and private stakeholders.

Alongside the World Bank/IMF Annual Meetings, our CEO Gary Forster presented our work to an audience at the Center for Global Development (CGD) in Washington DC. This was followed by a panel discussion exploring the key measurement and disclosure challenges that need to be resolved in order to make and track more mobilisation progress.

Click below to catch up on the discussion with Nick Anstett (Pollination), Chris Eleftheriades (Lion’s Head Global Partners), Margaret Kuhlow (US Department of the Treasury), Haje Schütte (OECD), Phil Stevens (FCDO), and Nancy Lee (CGD).

Other news

Here’s a quick roundup of other news and publications we’ve been reading over the last few weeks:

CONCORD has released the 2024 AidWatch report, examining official development assistance (ODA) spending by the European Union and its Member States. The report says that EU Member States inflate and divert ODA by channelling funds towards national economic and political objectives, and that over one in every five euros reported as ODA by the 27 EU Member States fails to meet the criteria defining ODA. It also reports that 50 years after the target was set, most European countries fail to meet the 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) commitment. In 2023, ODA from the 27 EU Member States totalled EUR 82.45 billion, representing 0.51% of their combined GNI. This is down from 0.56% in 2022. The report estimates that due to the cumulative shortfall in meeting the 0.7% target, partner countries have missed out on more than EUR 1.2 trillion in ODA.

Australia has launched a new portal to share details of its development funding. AusDevPortal is described as an online transparency portal, providing data on projects, finance and performance. Australia has also announced that it has re-started publishing data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) – a welcome move after its poor performance in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index. This was cited in the announcement by Pat Conroy, Minister for International Development and the Pacific, who expressed a determination to turn things around and improve Australia’s ranking in the Index.

A new Oxfam report examines World Bank climate finance and finds that, on average, actual expenditures on the Bank’s projects differ from budgeted amounts by 26–43% above or below the claimed climate finance. Across the entire climate finance portfolio, between 2017 and 2023, this difference amounts to US$24.28–US$41.32 billion. The report says that no information is available about what new climate actions were supported and which planned actions were cut. Oxfam warns that this makes it impossible to track and measure the impacts of the Bank’s climate co-benefits in practice. Oxfam recommends that the World Bank should improve its reporting practices, undertake a climate finance assessment on closed projects, standardise how it reports on climate finance in projects and create a public climate finance database.

In an opinion piece for All Africa, Hamzat Lawal argues for better transparency and accountability in climate finance spending in Nigeria to help attract investment. He calls for political commitment, a culture of accountability and clear, comprehensive reporting mechanisms that align with international standards.

“The major challenge we face in accountability and transparency in climate finance is access to data. So when the commitments are made, we cannot track them. We need to know not just how much has been pledged, but who is running the project, how much has been utilised, etc. Without such data, citizens and potential investors alike cannot follow the projects as they occur.”

The latest report from the Institute for Journalism and Social Change looks at spending in Africa by 17 religious US Christian Right groups, known for opposing sexual and reproductive rights. Based on analysis of the organisations’ financial filings, it finds they have increased their total spending in Africa by about 50% between 2019 and 2022 – totalling US$16.5 million over this period.

Devex has released a new report on the state of global climate financing – which analyses the climate funding of bilateral and multilateral donors using data from the OECD-DAC and Climate Funds Update. It focuses on ten of the countries most vulnerable to climate change, where their funding comes from, how it is spent, and how this compares to their needs.

New research from Recourse looks into where and how climate finance is spent by MDBs. It says MDB climate finance is funding fossil fuels and highly polluting projects, and failing to prioritise the most climate-vulnerable countries.

This CGD blog calls for greater transparency around international debt – from public and private lenders as well as borrower countries. It suggests improved transparency can help to reduce borrowing costs, looking at the example of Cameroon, and avoid the worst excesses of previous lending scandals.

ODA Reform has published three articles about the measurement of climate finance. Published ahead of COP29, they look at some of the methods for measuring climate finance flows, the lessons that could be learned from the US$100 billion target and the problems of setting measurement systems without an agreed methodology.

Unlock Aid has released its first Glassdoor for Primes report, which provides analysis of views on 26 of the largest development and humanitarian contractors. The report highlights how US foreign assistance flows through a relatively small number of organisations – more than 50% of USAID contract dollars go to just ten organisations, mostly based in and around Washington DC. Based on the survey responses of 80 sub-contracting local organisations, key findings include:

- Business practices across large prime contracting organisations can vary significantly. respondents said they were most likely to recommend working with Catholic Relief Services, Mercy Corps, and Save the Children. They favoured organisations which embrace transparency and open communication, fairness, genuine collaboration, and respect.

- Respondents rated many other large prime contracting organisations more poorly.

- Respondents said it was a costly and time-consuming process to prepare a proposal for a single prime contracting organisation. In addition, being included on a winning proposal was not a guarantee of funding and, on average, local organisations received 59% of promised funds – usually with delays.

An open letter from a group of Ukrainian civil society organisations is calling for concrete action on localisation. They say “the greatest obstacle remains a lack of transparency. We cannot determine how much funding is truly localised because the UN and most INGOs do not see reporting to the Ukrainian public as a necessity. This lack of accountability fosters distrust and prevents monitoring of progress.”

Devex has analysed how much development funding goes to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Using OECD-CRS and IATI data, the report (£) looks at funding directed to Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, the occupied Palestinian territories, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen. It finds that in 2022, bilateral donors disbursed US$13.8 billion to fund development and humanitarian activities in the region. Syria received the largest amount of ODA flowing to the region, about 14% of the total, and education was the priority sector in MENA.

A paper for the American Journal of Political Science reports on a conjoint survey across 141 low and middle income countries to elicit the aid preferences of elites who are uniquely close to development policy debates. The authors (Blair, Custer, and Roessler) find that “elites favour larger over smaller projects, grants over loans, and transportation infrastructure projects over initiatives focused on civil society or tax collection capacity. But contrary to the aid curse theory, elites also prefer projects with transparent terms and labour, corruption, and environmental regulations, and are at worst indifferent towards good governance conditionalities.”

A Climate Focus study, commissioned by the Family Farmers for Climate Action alliance, states that finance from the world’s two biggest climate funds is failing smallholder farmers. The analysis of 40 climate and biodiversity projects by the Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund in the agriculture and land-use sector between 2019 and 2022 found that although half of the funding was targeted at farmer-related activities, none of the money went directly to family farmers or organisations.

The consortium behind the Global Emerging Markets Risk Database (GEMS) has recently released new reports based on its DFI data, demonstrating that investments in emerging markets and developing economies are less risky than sometimes perceived. However, as this Eye on Global Transparency article reports, some private sector observers are calling for more detailed and regular disclosures.

A US Department of Defense Inspector General report has criticised the Pentagon for lacking documentation relating to US$1.1 billion of Ukraine spending. The report highlighted a lack of training and clear guidance as contributing to a lack of transparency, that limits the ability of officials to track if military aid was spent as intended.

Sign up to receive our newsletter direct to your inbox.