International Aid Transparency Initiative: Development assistance data at your fingertips

Ahead of tomorrow’s launch of the 2024 Aid Transparency Index, George Ingram, Senior Fellow, Global Economy and Development at the Brookings Institution has been investigating exactly what you can find out with International Aid Transparency Initiative data. This blog first appeared on the Brookings website.

Questions about development finance and activity take a number of forms, for example: What are donors doing and where? In which sectors are donors engaged? Can International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data be used to make decisions? What follows is a discussion and examples of how, with a little effort and care, one can mine the IATI database for valuable information and insights about where aid is going and for what purpose.

The foundation for letting in the light—for making aid information public—was laid in 2008 with the establishment of the IATI, a voluntary, multistakeholder compilation of data and information by public and private providers of development assistance. Donors were slow to buy into the concept, particularly as most had antiquated data systems that would require considerable updating and revision to meet the structure of the IATI data system. Initial participants were a few Western bilateral and multilateral donors who at first provided only a small amount of basic data. Progress has been slow but steady. And today, donor participation has expanded beyond traditional donors to donors who are not members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee, philanthropies, multilateral development banks, and international NGOs. The extent and quality of the data and information now has reached a point that IATI is beginning to embody the original vision of aid transparency.

What donors are engaged in a country?

The U.S. Global Fragility Act (GFA) and the companion U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability are being implemented in four priority countries (Haiti, Libya, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea) as well as the Coastal West Africa region (Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Togo). I am in the midst of a research project focusing on implementation of the GFA, which began in 2022. As partnering with other donors is an element of the GFA’s strategy, the research includes identifying which other donors are providing assistance to each of those nine countries. Using the official donor database maintained by the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) was one option, but it is current only through 2022. CRS data available for 2023 is preliminary. Instead, I opted to search the IATI database, which has most data complete through 2023, some data available for the first part of 2024, and some planning data for future years. I am accessing the IATI data through d-portal.org, one of the more user-friendly IATI web portals.

Table 1, which shows information drawn from d-portal.org on the top ten donors to Mozambique, is an example of data available for each of the nine countries. As assistance to a country can fluctuate considerably from year to year, I used a three-year aggregate (2021-23) to determine the top ten. The second column shows expenditure data for 2023. The third column (planning data for 2024) provides an idea of what new funding may be available.

Table 1. Top 10 aid donors to Mozambique (millions of USD)

| Donor | 2021-2023 spend data | 2023 spend data | 2024 planning (budget) |

| World Bank Group | 1,758 | 609 | 1,427 |

| USAID | 1,021 | 354 | N/A |

| Global Fund | 788 | 297 | 251 |

| World Food Program | 442 | 142 | 167 |

| Gavi | 283 | 47 | 48 |

| Sweden | 234 | 78 | 56 |

| UNICEF | 216 | 4 | N/A |

| Canada | 204 | 52 | 43 |

| Germany | 185 | 85 | 75 |

| Islamic Development Bank | 165 | 40 | N/A |

Source: drawn from d-portal.org

My search revealed the following: Among the official donors to the countries of the Coastal West Africa region, the World Bank Group is the top donor in each country, while USAID ranks second in one country, eighth in another, and tenth in three countries. Other donors in the top ten in one or more countries are Germany, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada, U.K., the African Development Bank, and the Islamic Development Bank.

I won’t go into the full analysis here, but what if the principal official donors of assistance to Mozambique—the World Bank Group, USAID, Sweden, Canada, Germany—joined forces to work toward common objectives? That would total some $1 billion per year going for common purposes, supporting the type of scale necessary to have concrete impact. In Ghana, where the World Bank and the USAID are the two major donors, they could work together to lead the donor community to collaborate with government ministries and local civil society on common objectives. In other countries where USAID is a lesser donor, the U.S. should use the IATI data to identify other donors with which it might collaborate. Beyond that, what if the World Bank, as the largest multilateral donor, and USAID as the largest bilateral donor, worked in collaboration where there are commonalities in their respective strategies?

What donors/recipients are involved in a sector?

Reasons for wanting to know what donors are active in a specific sector or country can vary. Maybe an employee in a government ministry or a member of a community group needs to know what external organizations are operating in a particular location in their country. Or maybe a donor agency or a private company wants to avoid overlap or duplication, find partners with whom to collaborate, or find new opportunities within a sector.

I am particularly interested in donor activity that encourages expansion of digital access. I used IATI data to identify the major donors that are supporting digital government. Again, using the 3-year aggregate of 2021-2023, the top official donors are the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, USAID, UNICEF, UNDP, and the African Development Bank. On the site, each donor’s name links to a list of each project it donates to and the recipient country.

What about the other side of the coin—what countries are receiving support for digital government? Entering “digital government” in the search box brings up a list of 152 countries receiving assistance for the period 2021-2023, with the largest two being the Philippines (receiving a total of $1.8 billion) and Indonesia ($1.1 billion), followed by Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Albania. Clicking on the name of a country shows which donors are financing what projects.

Project information

IATI data can also be used to find information on comparable projects. Perhaps an organization is looking for information, specifically evaluations, relevant to a malaria project it is contemplating in Zambia. Using “malaria” as a key word, IATI provides a list of 364 malaria projects, past and current, for Zambia. Each of these is accompanied by quantitative data, including results and financial information. Evidence of the potential of IATI data is revealed in some of the documents that are attached to these projects, such as the the USAID multi-country evaluation reports on the President’s Malaria Initiative.

Food security

Given the global prevalence of food insecurity and the need for robust and timely data to make policy and financial decisions, the World Bank has created the Global Food and Nutrition Security Dashboard. Using OCHA data for humanitarian assistance and IATI data for food security-related assistance, the dashboard provides information to donors, governments and civil society organizations in partner countries, and implementing organizations. Included in the mapping is information by country on the needs and level of assistance for emergency responses, financing, and emerging risks to better prepare the agri-food systems.

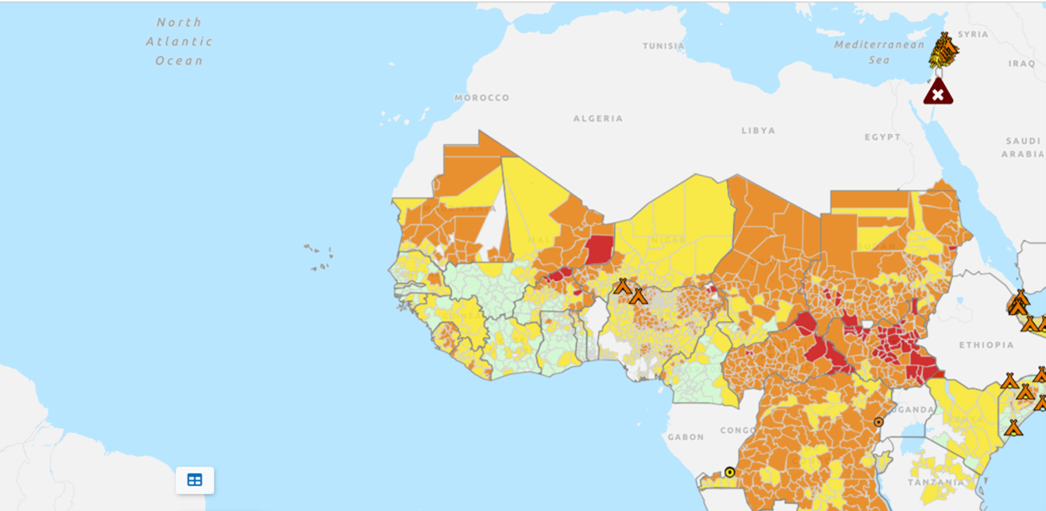

Figure 1. Global food and nutrition security dashboard

Source: Global Alliance for Food Security

For example, this map, one of several on the dashboard, gives the user information by country: the severity of food security (overall and by region); level of preparedness to meet food insecurity; amount of humanitarian assistance being provided; degree of inflation for food; and other, more detailed information. In the country profiles, there is information about funding by type, sector, donor, and amounts. Information about preparedness plans and future risks is also available. Through data sets and other information, decisionmakers and advocates can get real time information to help make urgent and informed decisions.

Conclusion

Despite having progressed to the point of useability, IATI remains a work in progress, and will continue as such until donors provide the full suite of data and information. Development practitioners should be turning to IATI as a valuable source of information in spite of its limitations, as increased usage of the data would serve as incentive for more donors to input higher quality data and make it even more useable.

To learn more about how IATI data can be used, attend or watch the July 16 launch of the 2024 Aid Transparency Index at the Brookings Institution.