How transparent is DFI climate finance?

Development finance institutions (DFIs) are increasingly pivotal in the climate finance landscape. As they channel more resources to climate finance, and prepare for a new global goal for low- and middle-income countries, Ryan Anderton investigates what exactly we know about current DFI climate investments. In short, he finds a messy picture. Enhanced transparency is crucial if we want to ensure that climate finance is valid, accountable and, most importantly, effective.

The focus on climate finance in 2024

Climate finance is a significant focus this year. The June UN Climate Meetings in Bonn, which conclude this week, mark the halfway point towards COP29 in November. During COP29, a new collective quantified goal on climate finance will be agreed upon – a global commitment on the amounts to be provided and mobilised for low- and middle-income countries.[1]

The previous commitment by high-income countries, made in 2009, was to provide $100 billion per year by 2020 (which was later extended to continue until 2025). High-income countries failed to meet this goal on time, causing frustration and mistrust among low- and middle-income countries. Recently released figures from the OECD DAC reveal that the target was met two years late, with $115.9 billion provided and mobilised in 2022.

There is no common definition or methodology for counting climate finance

However, many stakeholders have raised substantial concerns over the validity and accuracy of what is counted as climate finance, asserting that climate finance reporting is a mess. The root of this issue is the lack of a common definition and methodology for counting climate finance, allowing countries and multilateral institutions to decide for themselves what and how to count.

Reuters exposed how differing definitions have led to controversial projects being counted by high-income countries, such as a coal plant in Bangladesh and chocolate shops across Asia. The ONE Campaign has shown how various methodologies for counting climate finance can yield drastically different numbers, highlighting issues such as inflation (counting the whole amount of a project as climate finance even though only a portion of it should be) and counting what is agreed beforehand (commitments) rather than calculating what is actually being provided (disbursements).

The $100 billion agreement stated that climate finance would be from “new and additional” resources. However, the Center for Global Development (CGD) reveals that the lack of defining and calculating this could mean that around a third of the $100 billion is being counted when it arguably shouldn’t be. Oxfam has also claimed the reported numbers are inflated and raises the issue of whether grant-equivalent amounts should be counted rather than larger full loan amounts, which have to be repaid with interest to high-income countries.

“Transparency and good data are essential to inform, monitor, and track financing towards the new goal.”

The size and structure of the new climate finance goal

There are two key issues for the new climate finance goal: a significant increase in climate finance is needed; and better structures and systems must be established to improve transparency and accountability.

The new finance goal is likely to be much higher than the previous $100 billion, with consensus that it should be linked to the needs of low- and middle-income countries. UNFCCC’s 2021 report on the determination of needs estimates that over $5.8 trillion is required by 2030 to cover climate action plans, noting that the actual figure is likely to be much higher as the estimate only covers 42% of the total plans that had financial estimates. An updated report on the determination of needs is due later this year. The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance estimates around $1 trillion in external finance is needed by low- and middle-income countries per year by 2030.

Transparency and good data are essential to inform, monitor, and track financing towards the new goal. The ongoing UNFCCC discussions have emphasised the importance of having consistent and valid approaches and methodologies, more transparent reporting, and better data on climate finance flows. This should be implemented from the start of the new goal to ensure data comparability over time and to combat the issues mentioned regarding the validity and accuracy of what is being counted.

DFIs provide significant and growing amounts of climate finance

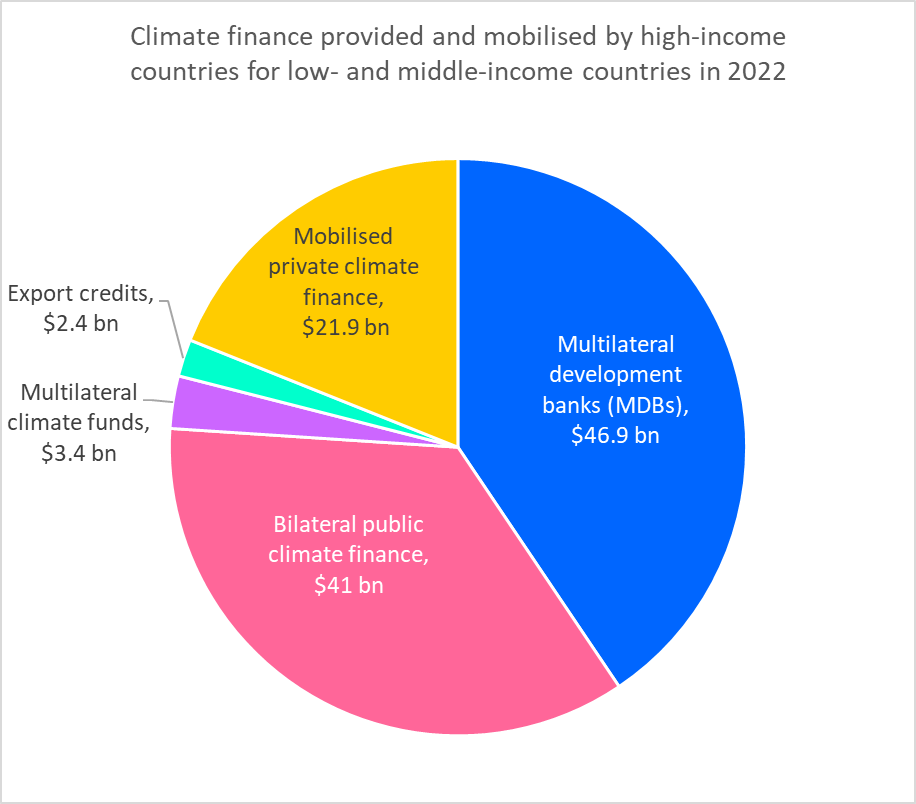

DFIs play a critical role in climate finance. In the global context, Climate Policy Initiative estimated that DFIs overall provided 57% of all public climate finance for 2021-22. OECD DAC statistics for climate finance from high-income to low- and middle-income countries show that multilateral development banks (MDBs) provided $46.9 billion out of the $115.9 billion for 2022, accounting for 40% of the total. Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine from the report how much bilateral DFIs contributed towards the $41 billion of bilateral public climate finance.

Source data: OECD (2024), Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2022, Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/19150727-en.

Contributions from DFIs are growing, and there are broader calls, expectations, and ongoing efforts for them to do more. MDBs have collectively exceeded their targets. In 2019, a joint statement by MDBs set an expected collective total of $50 billion in climate finance for low- and middle-income countries by 2025. This target was already reached by 2021, with finance increasing to $60.9 billion in 2022.[2] For bilateral DFIs, EDFI (a group of fifteen European DFIs) announced that $3.3 billion in climate finance was committed in 2021, marking almost a 50% increase for the second consecutive year. Climate finance from the US bilateral DFI – DFC – grew from $500 million in 2020 to $3.7 billion in 2023, which was almost a third of the US Government’s total contribution last year.

DFI reforms and capital expansions are also under discussion and being enacted to unlock more climate finance. Some DFIs are altering their fundamental goals towards climate action alongside development and poverty reduction. The European Investment Bank (EIB) has labelled itself as the EU’s ‘climate bank’. The World Bank, by far the largest climate finance provider, adopted a new vision “to create a world free of poverty on a livable planet” and announced its climate finance will increase from 35% to 45% of its portfolio. In response to calls from the G20 Independent Expert Group and the Bridgetown Initiative, some DFIs are starting to undertake capital adequacy framework reforms to unlock more available capital. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) claimed to unlock $100 billion in additional financing from reforms last year.

DFI climate finance lacks transparency

In this context of ever-greater financing from DFIs, how transparent are they about their climate finance? MDBs have, in some cases, been harmonising their approaches, which has been a welcome development to introduce some consistency. There are joint methodologies for counting both mitigation and adaptation climate finance. These approaches have somewhat addressed the validity and accuracy issues raised. For instance, the methodologies count the specific eligible activities within a project rather than inflating the climate finance amount to the whole project. There is also an annual joint MDB report which shows how much each MDB is committing overall and where it is being directed. However, these reports lack project-level information. Some MDBs, such as ADB and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), have project databases for climate finance and occasionally more information on project pages. But this is not consistent enough or widespread across all institutions. Detailed project information is vital for stakeholders to hold DFIs accountable, both for tracking flows and verifying claims, and to understand the investment impacts, outcomes, and learning what is and isn’t effective.

The state of climate finance transparency from bilateral DFIs is poor. High-income countries report bilateral public climate finance figures to the UNFCCC in their biennial reports, including for their bilateral DFIs. In many cases, the reporting for DFIs in these reports is more opaque than for most other bilateral climate finance, such as through aid agencies. For instance, for the British (BII), Belgian (BIO) and Swedish (Swedfund) DFIs, only a total annual climate finance figure was reported, whereas details are provided on individual investments through other sources. For the UK, 16% of its total bilateral climate finance for 2020 was counted as being directed through BII, yet it was only reported as one line item out of 266 items in total. Many bilateral DFIs do not disclose sufficient information themselves for stakeholders to verify how much and what is counted as climate finance. Some DFIs announce annual climate finance figures, but many do not publish any project-level climate finance data on their websites, making it almost impossible to verify and thus offering little accountability.

“Without sufficient transparency, especially at the project level, it is hard to verify claims and to see the actual impacts of climate finance, ensuring it goes to the right places and has the desired outcomes.”

Conclusion: DFIs need to be more transparent so that we can understand and reliably track investments and impacts

Based on our initial research, it’s clear that the transparency of climate finance is currently lacking. DFIs need to be more transparent. At the very least, DFIs should explain their methodologies and disclose which projects have climate finance, the amounts, and the reasons for counting them as such. Transparency is the cornerstone of building trust, ensuring reliable and valid counting and reporting, accountability, and learning. Without sufficient transparency, especially at the project level, it is hard to verify claims and to see the actual impacts of climate finance, ensuring it goes to the right places and has the desired outcomes.

With climate finance becoming even more of a priority for DFIs and the new global goal being agreed later this year, it is essential that we can understand and reliably track investments and impacts.

Holding DFIs to account through the DFI Transparency Index: join the consultation

We will continue to advocate for DFI climate finance transparency and hold DFIs accountable as part of our DFI Transparency Index. We are currently conducting a methodology review for the 2025 DFI Transparency Index, where we are consulting on integrating new climate finance indicators. You can register to join these specific consultation sessions on Tuesday 25th June at 3pm (BST) here or Thursday 27th June at 1pm (China Standard Time) here.

[1] Although the UNFCCC and OECD use the country groupings ‘developed countries’ and ‘developing countries’ for the international climate regime and the provision of climate finance, Publish What You Fund is moving away from terms such as these. In this blog we therefore use the terms ‘high-income countries’ and ‘low- and middle-income countries’ in place of these, respectively.

[2] This is higher than the $46.9 billion figure from OECD DAC statistics for 2022 because it is the total climate finance from MDBs, while the OECD DAC figure is the calculated share attributable to high-income countries.