Measuring the gap – international climate finance and the priorities of climate vulnerable countries – a proof of concept

Climate change threatens to cause major disruption to the environment and societies across the globe. The impacts of the changing climate will be heavily differentiated based on geography and the resources countries have to adapt to its effects in good time. This creates a triple-bind for some countries that are:

- Located in tropical or coastal regions or are particularly natural resource dependent and so are vulnerable to the effects of the changing climate;

- Low-income countries that do not have the resources to adapt and respond to these threats;

- The countries that have historically contributed the least to the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing the crisis.

There is a moral obligation on rich, polluting countries to provide effective financial support to help these countries, and this has formed a key part of the UN climate change negotiations. Rich countries pledged to provide US$100bn of climate finance per year to help poorer countries mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change.

Mitigation finance supports projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as renewable energy projects, low-carbon transport infrastructure and protection of forests and other natural “sinks” that absorb carbon dioxide. Adaptation finance supports projects that help countries adapt to the effects the changing climate will have on their populations. This can include climate resilient infrastructure (roads, buildings), water and irrigation in drought prone areas and support to livelihoods, insurance and other assets that reduce people’s vulnerability to more extreme weather patterns.

The US$100bn pledge has led to a series of challenges that are central to the global response to the climate crisis:

- Have rich countries delivered on their promise, and how can we reliably measure and track this?

- Is the finance allocated fairly, and is it effective at meeting the needs of poorer, climate vulnerable countries?

- Can the countries that are parties to the global efforts to respond to the climate crisis work together to meet the challenges and avert the worst potential scenarios?

Key to answering these questions is the transparency of climate finance. Good climate finance data will allow us to track progress towards the US$100bn goal (soon to be replaced by a new, more ambitious target, effective from 2025), to see how funding is being allocated and judge whether this is fair and effective. This will contribute to building trust between rich and poor countries – a vital ingredient in the climate negotiations.

Our initial research suggests that current transparency practices are characterised by a lack of standardisation, unclear definitions and multiple, fragmented information sources. This muddies the picture of who contributes and receives climate finance, how much is given and what it does.

We’ve developed an approach for analysing identified needs at the country level against international donor efforts to provide climate finance. Here we share an example of this approach using data from Kenya.

Kenya’s climate adaptation needs

Developing countries outline their climate change adaptation and mitigation priorities in a number of official documents that are produced as part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process. These are generally coordinated and aligned with other national development plans and they are developed cross-sectorally by a number of government ministries and agencies. Most governments have a climate change directorate, or secretariat, which leads the process.

Reporting on needs is uneven and inconsistent between developing countries. The level of detail and specificity of identified needs varies greatly depending on the available information and capacity to carry out needs assessments. Needs can be outlined in a number of documents[1] and may be costed by sector, by strategic priority, by project, or un-costed.[2]

We reviewed three key documents available for Kenya – the National Adaptation Plan (NAP), National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) and Kenya’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). We primarily used data from the NAP for this analysis.

The Kenya NAP provides a costed breakdown of priority actions for adaptation by sector for the 2015-2030 period. Sectors include areas such as infrastructure, energy, water and sanitation, housing and tourism. It identifies short, medium and long-term actions and provides a budget for each sector.

Kenya’s climate adaptation finance

We have used a dataset that comprises all transactions with the recipient country Kenya recorded in the IATI Standard from 2015-2021, alongside spending data from the OECD DAC CRS, and data from the ODI Climate Funds Update (which includes projects funded by the Green Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, Adaptation Fund and other climate specific multilateral funds). Where there is overlap between donors reporting to the OECD and IATI we have selected the strongest data from the two datasets and discarded the other. This has resulted in a dataset with 110,000 transaction lines in total.

To identify climate finance transactions we used the Rio Marker climate finance policy markers for adaptation spending (OECD policy marker 7) which can be marked with a significance of either 2 (principal), 1 (significant) or 0 (not targeted). We also carried out a word search for “climate” and “adaptation” (and their equivalents in five other languages) in activity titles and descriptions. We recognise there are likely inaccuracies where this word search has returned some false positives – titles or descriptions that refer to climate for other reasons – and have made efforts to manually check the data for the largest projects in our analysis. A full research project would involve the manual checking of all of the word-search identified activities.

Finally we have screened transactions and activities that use other policy markers or sector codes including the World Bank IDA climate change and adaptation sector codes, activities identified as contributing to SDG 13 (Climate Action) and other non-standardised policy markers that identify climate finance.

Where markers identify that a proportion of funds contribute to climate adaptation goals we have counted the total transactions proportionally (where a specific percentage is given, such as the case of the World Bank sector codes). With the “significant” Rio Marker, we have followed the high-end estimate from the approach taken by Oxfam in their climate finance shadow report and estimated these at 50% of the total project cost.

Where projects do not identify the proportion of the project that supports climate action we have counted the total transaction amount as climate finance. This means we may be overestimating in some cases. On the other hand there may be projects that contribute to climate change adaptation that are not included in our analysis because they are not marked or do not mention climate change in their project titles or descriptions. This means we may be underestimating funding amounts in other cases.

This reflects a principle of being guided by the stated intentions of the aid organisation in their official data. There are also limitations in the data itself which varies in quality across publishers, with some not using policy markers and some variation in the quality of titles and descriptions.

Analysis

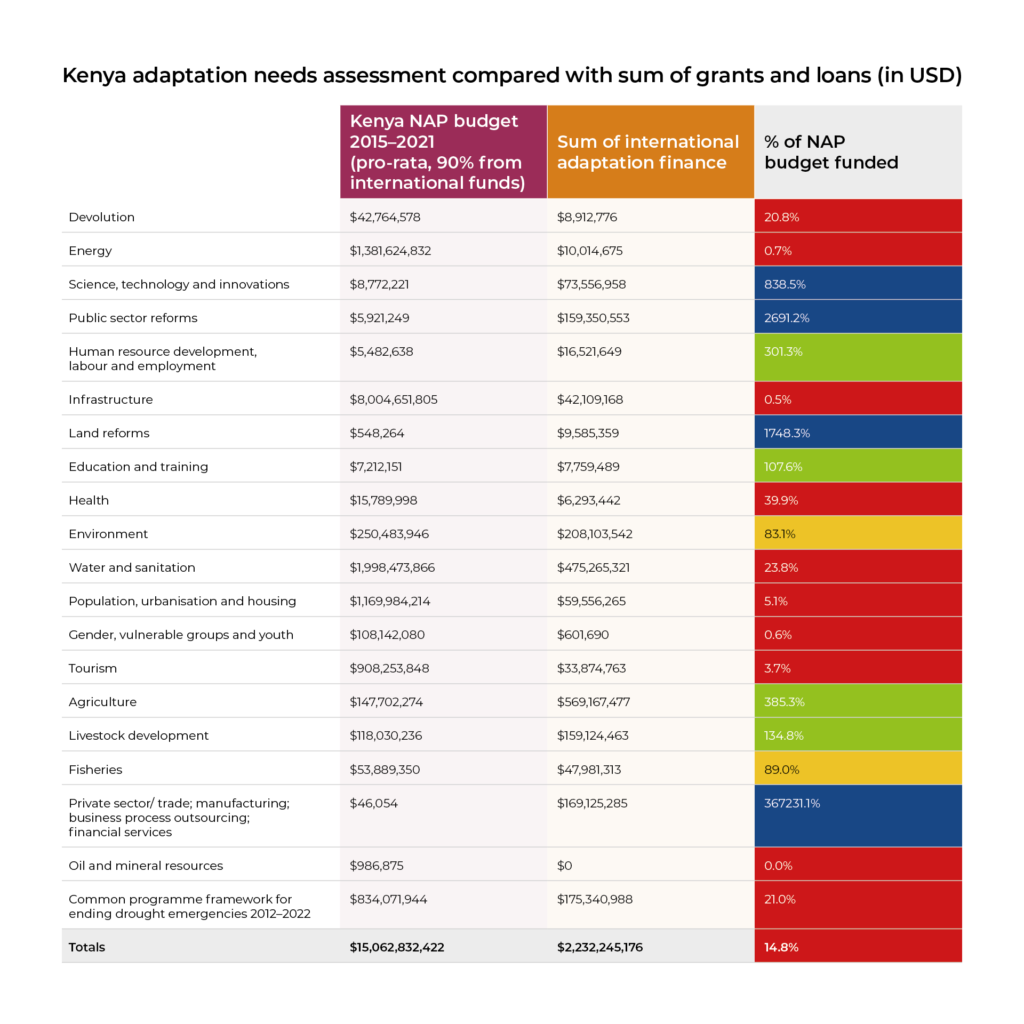

We took the costed adaptation needs budget from the National Adaptation Plan and compared this with 2015-2021 aid flows. The following table uses the official accounting method under the UNFCCC definitions of climate finance, counting loans at face value:

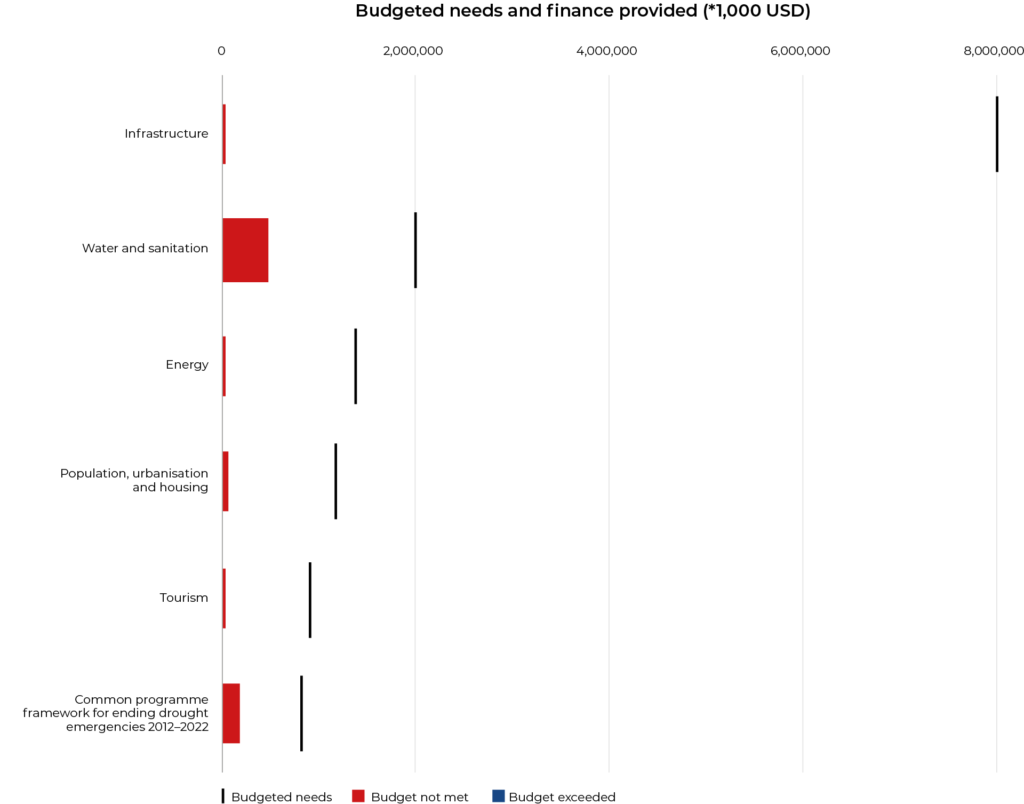

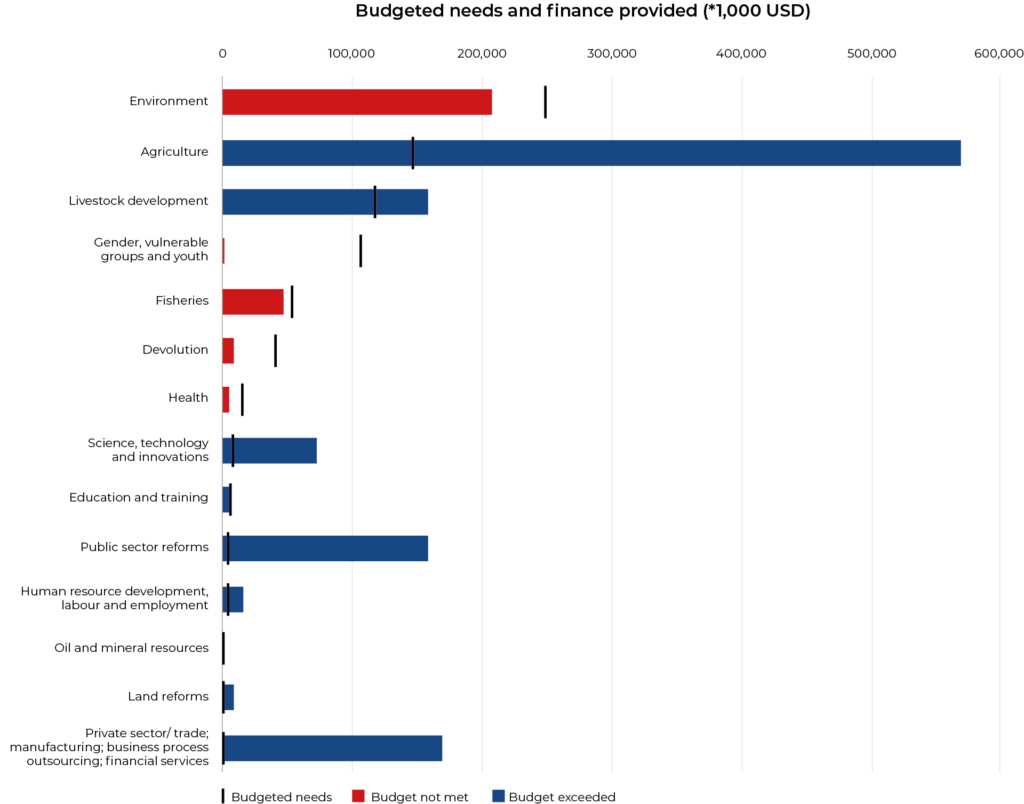

Total climate financial flows we identified supporting adaptation in Kenya were US$2.232bn from 2015-2021. This is 14.82% of the total identified needs in Kenya’s adaptation budget, meaning that funding is currently 85.18% behind (a shortfall of US$12.83bn). The total funding is made up of US$902 million in grants and US$1.33 billion in loan commitments (at face value). The following graphs illustrate where international funding has fallen short of the budget and where it has been exceeded. The first graph is the six items with the highest budget (and the scale is in billions of dollars). The rest of the line items are on a second graph using a smaller scale (hundreds of millions of dollars).

Graph 1: the top six budgeted items from the plan (scale in USD billions)

Graph 2: the lower budgeted line items (scale in USD hundreds of millions)

The dataset we built for this research contains detailed information about the activities contributing to each line item and we can use this to carry out further alignment analysis.

Focus on the energy sector

The energy sector is an area where there is an acute adaptation finance gap. The Kenyan government has identified efficient, reliable and accessible energy supply as fundamental to the Kenyan economy and a priority for adaptation finance. The total need identified in the NAP for 2015-2030 is US$3.51bn. Taken pro-rata for 2015-2021, and with 90% of the budget being subject to international finance, the total adaptation finance needs are US$1.38bn. So far just US$10m of adaptation finance has been recorded for the energy sector, just 0.7% of the total required.

One reason for this low amount is that energy is often not included in adaptation plans by international funders. While there is significant funding to energy projects in Kenya much of this is either tagged as climate change mitigation, or not tagged as climate finance at all. For example, a number of major funders, including Japan, France, Germany, the US, the EU and the World Bank have contributed significant finance to the geothermal energy projects (power stations and distribution) in Olkaria but have either tagged this as climate mitigation finance only, or not identified it as climate finance at all. This warrants further exploration, including considerations of whether funds are new and additional to existing aid and development finance commitments, and how funds that contribute to both climate mitigation and adaptation should be counted using the various marking and accounting approaches.

An example of an energy project that has been adaptation marked is the REACT programme funded by Sweden’s SIDA. This is a five year (2017-2023), 400 000 000 SEK (US$40m) project supporting small and medium enterprises to provide renewable energy and energy efficiency services to improve the lives of poorer sectors of Kenyan society. Sida has marked the project with a “principal” mitigation marker and a “significant” adaptation marker. During the period we reviewed Sida recorded $5.85m of commitments to the project, which we counted at 50% based on the use of the “significant” marker. They have published some results aggregated at the regional level: from the 2020 annual report, they reported 188,435 people with new or improved energy access against an annual target of 232,392 people (81%).

Next steps

We would like to broaden and deepen this analysis, carrying out an in-depth review of climate finance (both adaptation and mitigation) in three climate vulnerable countries. By building detailed datasets of climate finance we can help to identify where there are significant gaps or where there is duplication of aid money in other sectors. We believe this work will be of particular interest to governments, civil society and aid donors in these countries who will be able to use the data to see how climate finance aligns with identified needs. Where governments have identified specific examples of projects in their needs analyses we can use the detailed project-level data to see where these have been responded to and where funding is still required. This will contribute to greater agency for low-income countries receiving climate finance and a clearer understanding of what is being provided. Through this work we will identify issues with current reporting approaches and datasets and advocate for improvements in transparency of climate finance, as well as providing a methodology for future similar analyses.

Read our detailed concept note: Climate Finance: Is it Transparent, Impactful and Aligned to National Priorities?