The illusory promise (and real potential) of new DFI impact management tools

At the start of November 2021, Publish What You Fund’s DFI Transparency Initiative marked a new phase in our project with the launch of our DFI Transparency Tool and our report Advancing DFI Transparency. To accompany the launch, we are publishing a series of blogs that discuss the process of developing the tool and introduce its key components. In the first blog of the series I reflected on the two years of research that have informed the creation of the tool, while the second blog introduced the first of its components: core information. This blog moves to the second component of the tool, impact management, and reviews the development of new impact management tools.

Our second working paper studied the disclosure patterns of policies, processes and data related to impact management of DFI investments. One of our key findings was that there was a trend towards the development of new impact management tools that combined ex-ante impact prediction with ex-post measurement and evaluation. Following the advent of relatively rudimentary impact management systems around the turn of the century, there has been a more recent wave of new tools that have developed in light of demands that DFIs better orient their activities towards clear developmental impacts. Notable new systems include IDB’s Development Effectiveness, Learning, Tracking and Assessment (DELTA) tool, IFC’s Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring (AIMM) system, and DFC’s Impact Quotient (IQ) tool. The tools provide frameworks for the prediction, monitoring, and evaluation of the development impact of investments. They also tend to generate a single metric – for the purposes of this blog we will call it a “development score” – that is an aggregation of ex-ante impact predictions and is designed to give an indication of the overall development impact of an investment.

This blog argues that calls for the disclosure of the development score that these tools produce is misguided as these scores mask the granular ex-ante and ex-post impact data that is being generated. The most important and relevant information are the underlying metrics, both ex-ante and ex-post, that give stakeholders a clearer picture of both the estimated development impact and the actual results of the investment. The value of the new impact management systems lies in the fact that they establish a framework for the production and collection of this data, and we think that this should be the focus of disclosure efforts.

The demand for ex-ante “development scores” – are they really worth it?

As mentioned above, one common feature of the new impact management tools is the production of development scores that indicates the potential of an investment to produce positive impacts. In addition to the above systems, tools that produce a score include DEG’s DERa and EBRD’s ETI. During the course of our research we heard numerous calls for various DFIs to disclose these development scores for each of their investments. The allure of such a metric is easy to understand: it promises to summarise the totality of positive (and in some case negative) effects of an investment within a single score that appears to be immediately comparable across the portfolio of the institution. However, if too much value is placed on these scores the promise quickly becomes illusory. One key problem with the production of single scores is the fact that it can be hard to ascertain what factors contribute to the score and the relative effect of factors.

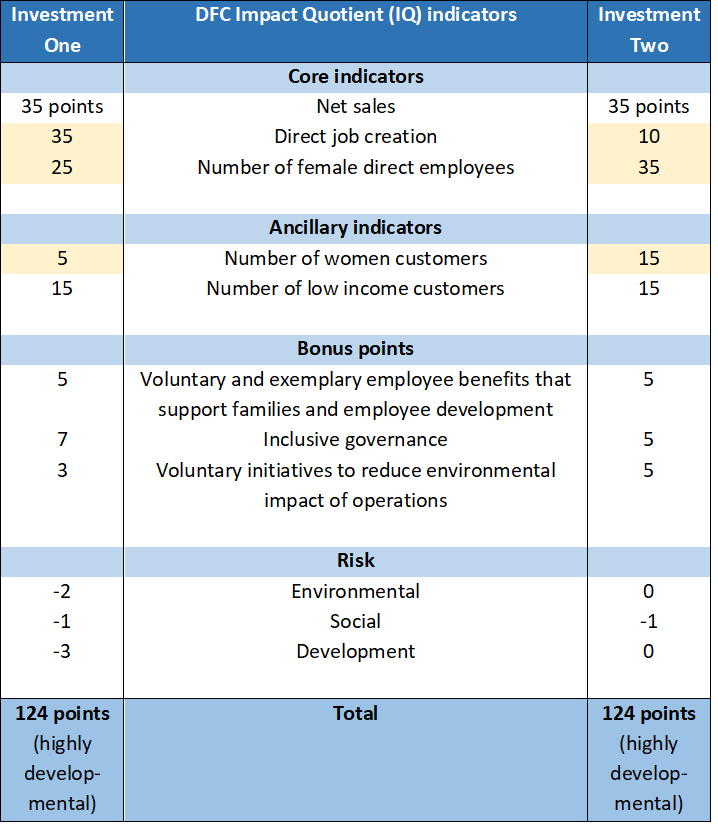

Taking DFC’s IQ as an example, the score is a result of a selection of up to three core impacts, two ancillary impacts, bonus points, and is adjusted according to environment, social, and development risk. The fact that DFC’s system incorporates such a range of impacts is undoubtedly to be applauded, yet it also means that the final score tells you nothing about the contribution of each individual impact. It is quite possible that two investments could be assessed according to identical criteria, have the same IQ scores, yet perform differently on individual indicators. This could play out as follows:

On the face of it, both Investment 1 and Investment 2 have identical levels of development impact. However, as can be seen, the contributions that the individual indicators make to these scores vary significantly. This is important because it obfuscates important information that could be indicative about the successfulness of particular investments in a given scenario. For example, if both Investment 1 and Investment 2 were made in a country with relatively high levels of employment but low levels of gender equality, it may be appropriate to promote Investment 2 as the more appropriate intervention as it scores higher on both number of direct female employees and number of women customers. This is important information for stakeholders who wish to evaluate the gender dimensions of the two investments and to deploy lessons from the investments for future interventions.

Impact management systems as a framework for disclosing ex-post results?

The production of development scores is not the sole focus of newer impact management systems however. Systems such as DELTA, AIMM, and IQ also establish how the DFIs that use them will monitor the impact of their investments on an ongoing basis. This is important as it confirms that DFIs are collecting (or have started collecting) relevant ex-post impact data that, with the correct agreements and systems in place, could be disclosed. This, we argue, is the real promise of new impact management systems.

Two systems – those of IFC and DFC – arguably move a step beyond this commitment to monitor the impact of investments by offering insights into the types of indicators that will be used to assess investments. Of the two systems, IFC’s AIMM is arguably the most developed in this respect. IFC have developed over two dozen Sector Frameworks (of which twenty are disclosed) that give large amounts of information regarding indicators used to measure impact. In addition to defining “project outcome indicators” and “contribution to market creation indicators”, the Sector Frameworks provide metrics that contribute to a “gap analysis” that determines the development needs for various potential impacts. This type of development is important as it provides granular insight into the way IFC intends to measure the impact of their investments.

The DFI Transparency Tool contains a number of indicators that encourage the disclosure of granular impact data. Our research has shown that disclosure of information in line with the tool is ambitious but achievable. Furthermore, stakeholders have identified the information defined by the tool as important, highlighting the need for DFIs to act now to improve their disclosure. Among other reasons, this will help DFIs to demonstrate the development impact that their investments may have or have had and allow other stakeholders the ability to measure the value of these investments. The tool has received the support of a number of stakeholders including the EBRD and DFC at the launch event. To further encourage change within the sector we will be using the DFI Transparency Tool as the framework through which we will analyse the transparency of leading DFIs during 2022. Over the next few months we will be consulting on a methodology for this analysis with a view to publishing an initial assessment and ranking in a year’s time.

Further reading:

Transparency of financial information: The key to increasing development flows

Why do DFIs invest in financial intermediaries and why do we need to know more?