If DFIs are truly committed to openness and accountability they should publish all environmental and social documentation

At the start of November 2021, we marked a new phase in our DFI Transparency Initiative with the launch of our DFI Transparency Tool and our report, Advancing DFI Transparency. To accompany the launch, we are publishing a series of blogs that discuss the process of developing the tool and introduce its key components. In the first blog of the series Paul James reflected on the two years of research that have informed the creation of the tool, the second blog introduced the first of its components: core information, and the third blog reviewed impact measurement processes for the second component of the tool: impact management. This blog continues on to the third component of the tool: environmental, social and governance (ESG) and accountability to communities, and reviews the rights-based approach for access to information.

Our third working paper scrutinised the ESG disclosure requirements and practices of development finance institutions (DFIs) and explored the accountability mechanisms they have in place. A key finding was that detailed ESG documentation produced for projects was rarely disclosed by most DFIs. DFIs argue that one of the main additional benefits they provide is to improve the ESG standards of the clients that they invest in (development additionality), therefore they should lead the way with ESG and accountability. However, it is hard to verify if DFIs are doing this when they are not disclosing the documentation they have and are not being transparent and accountable to the public, most importantly to project-affected communities. This blog discusses the encouraging signs for the right of access to information for DFI accountability and what needs to happen next to promote further openness and prevent back-sliding.

The right of access to information

A previous guest blog by Fran Witt and Fidanka Bacheva-McGrath provides great detail about the right of access to information, which is articulated in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Movement concerning this right has consisted of two main components – regional laws and regulations which require institutions to disclose more information to the public and pressure from the civil society community for DFIs to recognise this right and implement the laws. For instance, the Aarhus Convention in Europe came into force in 2001 and established that everyone has the right of access to information on environmental matters held by public bodies. The Escazú Agreement in Latin America and the Caribbean came into force in 2021 and established similar rights.

Are DFIs disclosing more ESG information?

The response by certain DFIs to the pressure and obligation for increased access to information has been positive, albeit with caveats. Some DFIs have made commitments to disclose more information than they have previously even if many do not explicitly recognise access to information as a right. One big change has been in policy, with some DFIs transitioning to a presumption of disclosure, moving away from a presumption of non-disclosure. This has been characterised as a transition from a procedure-based approach to a rights-based approach. The idea behind this is that information and documentation should be made more readily available and that it should be released provided there are no legitimate reasons not to do so. The European Investment Bank (EIB) is an encouraging case study; it set up a Public Register in 2014 to disclose ESG documentation for projects. Although there are questions about whether everything is released in the Register (which would arguably contravene the Aarhus Convention) it is a step in the right direction which not many other DFIs have done.

However, there have been questions about whether presumption of disclosure has indeed been the great leap forward for transparency as was hoped. Without recognition of access to information as a right and a commitment to pro-active disclosure of all information (with a legitimate list of exceptions), then how DFIs act may go against the principles of openness and accessibility. For example, although the Asian Development Bank (AsDB) has a presumption of disclosure policy there are concerns that the way it currently acts has led to a decline in the amount of information that is pro-actively disclosed. During our research an interviewee noted that the AsDB automatically discloses fewer documents to its website under its new policy, instead only disclosing them when they are specifically requested. With a presumption of disclosure approach it means that all documents should be disclosed when requested (provided it does not fall into its broad list of exceptions) but is this sufficient to be transparent in a truly open and accessible way and to respect the public’s right to information? Major issues with relying on such information requests include that it can take significant time and resources (thus it may not be disclosed in a timely fashion) and people have to know that something exists to even be able to request it. As our research findings show, DFIs often don’t clearly communicate what ESG documentation has been produced for projects.

What do DFIs need to do to improve public access to ESG information?

A presumption of disclosure policy is encouraging (at least on paper) and more DFIs should adopt this approach. However, for DFIs to show they are serious about a rights-based approach and to truly respect the right of the public to access information, then ESG documents need to not just be more available in theory, DFIs also need to pro-actively make this information available in a more accessible and open manner. Consequently, DFIs should adopt automatic and systematic pro-active disclosure of all ESG documentation for all projects making sure it is available and accessible for all. More comprehensive disclosure on the part of DFIs has the potential to pre-empt access to information requests and ensure that rights are respected without need of recourse. The EIB has started this journey, and other DFIs need to follow suit and go further, not waiting on regional laws and regulations to require them to do so.

How will the DFI Transparency Tool help to improve access to ESG documentation?

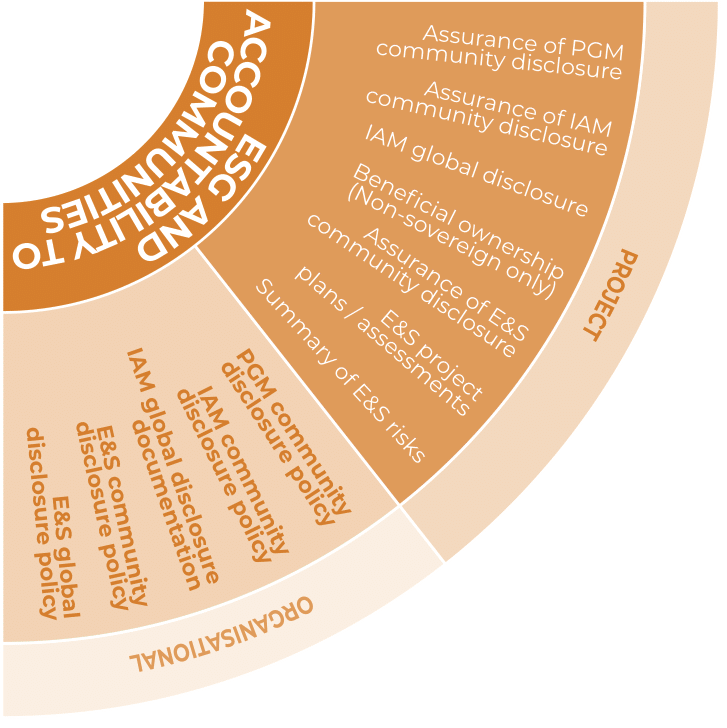

The DFI Transparency Tool provides granular guidance on the types of ESG and accountability information that as a minimum DFIs should disclose about their investments. Disclosing in line with the tool will enable DFIs to improve transparency practices and make them more accountable to the wider public. Furthermore, it provides a framework for the assessment of DFI transparency.

The tool requires the DFI to reveal what ESG documentation is produced for every project. This would make them more open, build trust, and help them comply with laws such as the Aarhus Convention and Escazú Agreement. The tool then allows us and others to verify whether these documents are disclosed on a public registry as they should be, and if not then at the very least people will be able to make information requests for specific documents they know exist.

Our research has shown that disclosure of information in line with the tool is ambitious but achievable. Furthermore, stakeholders have identified the information defined by the tool as important, highlighting the need for DFIs to act now to improve their disclosure. Among other reasons, this will help DFIs to show the potential ESG risks that their investments may/have had and allow other stakeholders to hold DFIs accountable for how they manage and mitigate these risks. The tool has received the support of a number of stakeholders including the EBRD and US DFC at the launch event. To further encourage change within the sector we will be using the DFI Transparency Tool as the framework through which we will analyse the transparency of leading DFIs during 2022. Over the next few months we will be consulting on a methodology for this analysis with a view to publishing an initial assessment and ranking in a year’s time.

Further reading:

The illusory promise (and real potential) of new DFI impact management tools

Transparency of financial information: The key to increasing development flows

Why do DFIs invest in financial intermediaries and why do we need to know more?