Who funds women’s economic empowerment – a data journey

The data challenges of mapping funding flows to WEE

Introduction

Reading a diversity of sources can provide a more complete picture on a topic. For example, piecing together information from official news sources, interviews and specialized research takes more time, but rewards with a fuller view of the facts. With this principle in mind, we have designed the Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) project to collect data from a wide variety of sources in order to more thoroughly track the funding going to WEE and it’s subcomponents women’s financial inclusion (WFI) and women’s empowerment collectives (WECs).

Here we’ve set out our journey to access, merge, clean and use unique datasets on funding flows for Women’s economic empowerment in a way not done before. We will use the evidence to inform recommendations and advocacy for increased and better funding for women.

Research context

Publish What You Fund and others such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC)’s GenderNet, Donor Tracker and Oxfam have already made notable efforts to improve the tracking of funding flows for gender equality and WEE. Building on these efforts our aim is to produce granular findings on who funds WEE, WFI and WECs, the breakdown of funding to specific aspects of each and trends over time. For this we require detailed project level information.

So, what data sources did we use?

We have collected data from four sources across the period 2015-present (where these were available). These were:

- Data from the OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) (2015-19)

- Data from donors publishing to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) (2015–present)

- The CGAP Funder survey data (2015–19)

- Candid data (2015–present)

Together these sources provide richer information on funding flows. In addition to the data from major donors within the OECD-DAC member countries we have data on activities further down the aid chain (for example activity details from NGOs and women’s funds); from non-traditional donors and data from large US and global philanthropies.

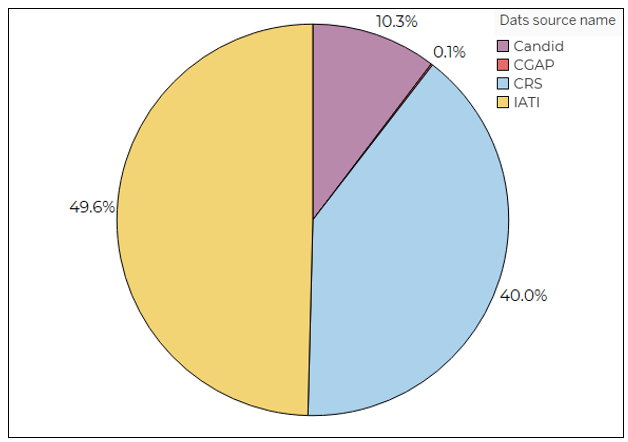

With these sources we are building six country datasets to analyse spending trends in a new way. The pie chart below gives a sense of the data source split in Kenya.

What challenges did we face?

There were several challenges which our data collection methodology had to overcome:

Downloading data: We ran into some challenges sourcing all of the IATI data which we required for our research and had to develop an approach to extract these together. We had to use all four IATI data user interfaces:

- D-portal for the gender marker

- the Country downloader tool for the main data

- the Datastore classic for descriptions

- The Humdata portal for Covid-19 funding

Data quality: In order to effectively map the funding flows to WEE our methodology used qualitative data such as titles, descriptions and sector information to help identify our research sample. However, this approach was hampered by poor quality data with null values, incomplete data and data aggregated to sector or country level. We mitigated this by double-checking our search criteria and manually surveying activities to account for poor data quality.

Merging the data

In order to ensure reliability when merging the data sources, we identified a list of duplicate funders who publish across more than one data source in overlapping years. Tabled below is a count of the duplicated donors identified for Kenya, Nigeria & Bangladesh.

| Data sources | DAC-CRS | IATI | CGAP | Candid |

| DAC matches | N/A | 59 | 20 | 0 |

| IATI matches | 59 | N/A | 20 | 17 |

| CGAP matches | 20 | 20 | N/A | 1 |

| Candid matches | 0 | 17 | 1 | N/A |

Double counting

Within the IATI data, organisations from all levels of the aid chain publish their activities. This creates a potential double-counting problem when aggregating expenditure across organisations and activities. Spending of the same money can be published by multiple organisations as it passes through the aid delivery chain.

To avoid double counting, we developed a new approach which utilises the reporter and recipient name variables to identify double counts of activities. For example, the Netherlands MFA reports activities to IATI. All these activities will be left in the data but, any activities which are reported by another publisher (which is not the NL, MFA) but which lists the NL, MFA as a provider will be removed. This is under the assumption that if the NL, MFA is listed as a provider by another publisher that: 1. The NL, MFA is already reporting the activity and 2. the publisher has published only that activity in its entirety.

Data also needed to be cleaned and merged particularly where different code lists were in use to identify for example; sector types, finance types or organisation types across the different data sources. Fortunately, our two main data sources (IATI & OECD DAC CRS) use similar codes which made cleaning the data much quicker. A full outline of the data collection methodology can be found here.

Conclusion

To date we have built three unique country datasets which will provide us with new insights into funding from multiple sources in Kenya, Nigeria and Bangladesh. We will be repeating the exercise with three more countries (Pakistan, Uganda and Ethiopia) when phase two of our research begins.

These datasets and the background methodology to bring them together can provide useful insights into how these various data overlap. In addition, through our experience of collecting IATI data we encourage the IATI secretariat and the data community to continue to develop accessible user interface tools to provide full access to data for a wide variety of data users. Currently, a large amount of work and a high level of technical expertise are required to analyse funding flows from the available data. In order for others to replicate the WEE analysis approach the data needs to be made more usable and accessible.

Our findings will also be useful in determining how to best allocate funds and address funding gaps. We will use our evidence, working with policymakers, donors and gender advocates, to advocate for more and better funding to WEE, WFI and WECs.

Sign up to our newsletter for more findings on what we uncover in the data.

Related posts:

Donor financing for gender equality: spending with confusing receipts

Debt relief as ODA – why it’s looking bad for aid transparency