Three ways the international community can make gender equality work more transparent

This blog first appeared on the Brookings Institution website.

This week the Gender Financing Project launched the report “Making gender financing more transparent.” Brookings will host a launch event on Thursday, July 8 at 10:00 am EDT/3:00 pm BST to reflect on the data needs of gender equality stakeholders and how international donors and data platforms can meet them.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined that granular and intersectional data is key to “leaving no one behind” and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. In 2020, world leaders reignited the vision of the Beijing Platform for Action and committed to accelerate the realization of gender equality. This year, the G-7 leaders and countless others at the Generation Equality Forum emphasized that to build back better we must prioritize gender-disaggregated data and analyses to ensure that efforts are evidence-based and decision-makers are accountable.

What the past one and a half years has taught us

When we began our work in 2019, we already knew that tracking funding for gender equality efforts was a difficult task—and this was just funding from bilateral and multilateral sources of official development assistance (ODA). What was even harder to find were the other sources of funding for gender-related efforts, including from humanitarian, philanthropic, and development finance institutions. How are we to move forward to effectively meet the SDGs and COVID-19 inequalities with a fuzzy and incomplete picture of what is being funded, for what purpose, and with what results?

Our research started in Kenya, Nepal, and Guatemala. We wanted to understand the needs of a variety of gender stakeholders, particularly at the country level. Although there is a demand by national and local stakeholders for financial and programmatic data on gender equality issues—for programming, for coordination with other stakeholders, and for advocacy—there are many barriers to using this information. Most stakeholders are dissatisfied with the available data and information. Thus, while donors have spent considerable resources collecting and publishing gender equality data, the blockers to a robust uptake need to be addressed.

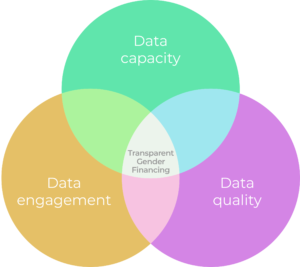

Our research, consultations, surveys, and discussions have led us to conceptualize that the road to better transparency requires attention to three interrelated but distinct concepts: data capacity, data engagement, and data quality.

It’s not enough, for example, to publish high-quality information if it is not accessible, in the wrong format, or costs too much to acquire. It is simply not enough to publish and believe that the job is done. Engaging with a range of gender equality stakeholders—especially women’s rights organizations and NGOs—is essential. Data is power and local gender equality stakeholders need to be empowered to use it for a variety of reasons and at different times in the program cycle.

Our report contains detailed recommendations to improve the transparency of gender financing and programmatic data. We have included a checklist at the end of the report that sorts these recommendations by both donors and by data platforms, which we hope is a helpful tool.

Three takeaways

1. High-quality data alone is not going to move the gender equality needle. Making data more accessible will.

We recognize that many donors have put significant effort into publishing gender-related data into a number of open data sources, most notably the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Creditor Reporting System and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). But the uptake of this data by national and local stakeholders has been minimal due to a few important restraints. For one, most stakeholders don’t have the resources and/or data literacy to utilize the often-complicated datasets and formats. Core funding for building data capacity is rare. As a result, either the data goes unused or local stakeholders depend on hiring outside—and often more expensive—staff.

2. Publication is just the first step. Engagement can shift power to local actors.

Data is the beginning of a conversation with relevant stakeholders—gender advocates, local and national governments, and international donors. If development is truly to be locally-led, data is a means to shift the power and decisionmaking to those who should be at the heart of the work. That means involving gender equality stakeholders at all stages of the program cycle—from priority setting, program design, and implementation to evaluation. This will have a positive effect not only on data quality but should also increase trust in and use of the data. Ultimately, proactive engagement and coordination with gender equality stakeholders will lead to the most important goal: better gender equality outcomes.

3. Donors should do more than utilize the gender marker—they should tell us why.

Many international donors utilize the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) gender marker, which indicates the extent to which a particular project is intended to support gender equality. As our report finds, not all donors apply the marker in the same way, and they don’t always apply it consistently across different platforms. We think the latter is something that can be fixed relatively easily. What would be a real step forward, however, is for donors to explain the analysis behind the specific use of the gender marker. OECD’s guidance for use of the marker outlines the gender analysis donors must conduct to determine which minimum criteria projects must meet before assigning any gender marker score. This underlying analysis, however, is not published, so there is no way for other stakeholders to understand why a particular score is published, who the intended target gender group(s) are, which of the project objective(s) aim to advance gender equality, and what indicators will measure progress. Publishing this information could have several benefits, including better coordination among donors, as well as a better push for gender-disaggregated results data.

As the global efforts to build back better hopefully take hold, especially for gender equality, let’s not underestimate the ability of good quality gender financing and programmatic data to underpin these goals. To accomplish that, however, local gender stakeholders need a central place in that discussion, armed with accessible, useable, and comprehensive data.