Untangling the UK aid cuts – a transparency journey timeline

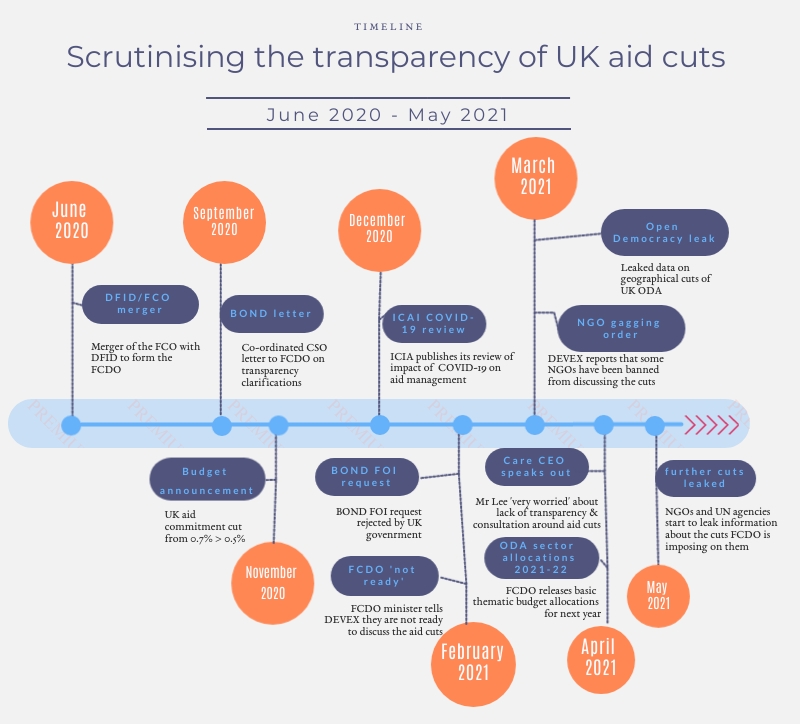

According to all advice, the best thing to do when planning for a change in your financial situation is to re-plan your budget. But what if you don’t know how much you will get next year, month or even next week? following the UK government announcement that it will reduce its aid commitment, this is the situation many aid agencies are now facing. In this blog we timeline the communication of, and reactions to, the UK government’s aid cuts and pose the question, is this a new era of UK aid transparency?

Aid under new management – May to October2020

As it became clear in 2020 that the UK’s economy was shrinking, the UK government’s commitment to spend 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) on official development assistance (ODA) meant that the aid budget was also going to shrink. Whilst Publish What You Fund has not been attempting to track the cuts, we have seen the UK’s international development community working together to build a picture of where and how cuts might fall based on the data available.

The 2020/21 aid budget saw planned cuts of around £2.9 billion, due to the GNI fall. Research from Save the Children in September 2020 uncovered, through an analysis of the budget figures, that activities previously attributed to the Department for International Development (DFID) bore the brunt of these cuts; the largest cuts were made to aid for education, agriculture and water & sanitation and were aimed at the countries in highest need such as Yemen (-54%) and Syria (-83%). Speculation on the impact of these cuts on the poorest countries, particularly humanitarian aid in conflict affected regions, made headlines across the UK.

In response to a lack of detail on the cuts, the UK network of international development partners known as BOND sent a coordinated letter to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020. It requested to open a communication channel and for the new department to re-commit to the transparency agenda as established by DFID, including for all ODA spending departments to reach ‘Good’ or above in our Aid Transparency Index. In response, the then Minister for Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development at the FCDO wrote to highlight their transparency and other commitments, but stopped short of committing to the standards enshrined in the former DFID transparency agenda.

Fall in UK ODA commitments – November 2020

Then, in November last year the UK Government announced that it would reduce its legally enshrined aid spending target of 0.7% of national income for the 2021 calendar year. These controversial cuts came on top of the already reduced aid spend due to the fall in UK GNI in 2020.

Further analysis of International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data suggested that these cuts could reduce the 2021/22 budget by a further £4 Billion and would continue to fall on more ‘social’ sectors such as children, health and education whilst aid to ‘industrial’ sectors such as banking, financial services, energy and industry would remain largely untouched or even increase, as set out by current commitments published by the FCDO. The aid cuts became further entangled when comparing the remaining budget with already published commitment figures (for example contributions to multilaterals) which far exceeded what is available in the remaining 2021/22 aid budget. In short, the publicly available figures following the cuts just didn’t match up, stoking fears of yet further cuts.

Changing priorities? – December 2020 to March 2021

The government’s approach to the aid cuts received further criticism when the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) released an Information Note in December on the impact of covid-19 on aid spending and management which highlighted the detrimental impact that the lack of transparency was having on developing partners’ ability to re-prioritise their work.

‘We heard concerns that the lack of transparency about the government’s prioritisation exercises hampered the ability of suppliers – who play a crucial role in delivering aid on the ground – to adjust their programmes.’[i]

Despite this finding, the UK government rejected an Freedom of Information request submitted in February 2021 by NGOs. The request for further details of the planned UK aid cuts was rejected on the grounds that the information falls under aid statistics which will be published later in the year and is therefore exempt from FOI requests. At this point, the transparency of the cuts, the policy justification behind them and their implementation had been almost absent with ministers claiming they cannot disclose information before final decisions have been made.

That the current government has a change of priority towards its ODA commitments is clear. The long-awaited policy paper: ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age’ the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy provided little detail on the future UK ODA spending trajectory. So, when leaked news of some of the geographic focus of the planned aid cuts were published by Open Democracy in March 2021 there was little surprise that conflict affected countries such as Yemen and Syria were top of the list, following the analysis of existing budget figures, but the scale of the cuts to these countries were a shock. News of the cuts prompted further aid data analysis from the One Campaign which demonstrated that together the cuts would constitute a 63% drop in bilateral aid since 2019. They found that, due to existing legally binding government commitments to multilaterals such as WHO, the World Bank and GAVI, core support for developing country national budgets would be cut and therefore dramatically decrease support for social sector spending such as family planning and nutrition in these countries.

Untangling the web- March 2021 to now

The attempts to untangle the web of aid cuts has continued against a context of decreasing government transparency more generally. In March 2021 the UK Open Government partnership warned that the government was no longer on track with its National Action Plan and was put in ‘under review’ status. This, coupled with rumours of an NGO gagging clause which limited the ability for stakeholders to discuss their cuts publicly means many development partners have been left in the dark. Care’s Chief Executive Laurie Lee was one of those most recently to voice concern at the delay in FCDO’s budget priorities being published and the lack of transparency on the cuts.

In April Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab did provide the FCDO’s thematic budget allocations for fiscal year 2021/22 ahead of an appearance at an International Development Select committee review. However, it has left many of us in the development sector with more questions than answers. The thematic breakdown provided did not align with aid data standards typically used by development actors so agencies still don’t know about where the long-term cuts will fall across geographic, programmatic or specific sectoral areas. The budget was also condemned for not being brought to a Commons debate.

As the government continues to grapple with the pandemic, and before its full economic impacts are known, we hope that ministers will soon start working with their development partners to effectively manage the aid cuts. The first step in this process is to be fully transparent about where and how cuts will be made. This is essential to ensure that the government maintains the high transparency standards set by DFID.

Related posts:

It’s time for the UK government to change track on aid transparency

Shrouded in secrecy: UK Aid cuts are happening behind closed doors, agencies warn

UK aid faces a serious transparency challenge following announcement of DFID and FCO merger

[i] https://icai.independent.gov.uk/news-uk-aid-spending-during-covid-19-management-of-procurement-through-suppliers/