Debt relief as ODA – why it’s looking bad for aid transparency

Since the 1960s there has been an international consensus on a common aid effort with the formation of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) – a group of 30 countries which regulates and reports on how international aid is spent. This effort includes guidance on sectoral spending and recipient countries in order to focus aid spending on the neediest areas. Guidance on the definition of Official Development Assistance (ODA) has regularly been modernised but a recent announcement by the DAC on new rules for how debt relief will be counted as ODA has raised questions around aid allocation and transparency in this area.

A looming debt crisis

The scale of developing countries’ debt has been growing again since the historic 2005 debt write off. The Jubilee Debt Campaign recently released their debt portal showing that today 51 countries are in some kind of debt crisis, up from 31 in 2018. The global coronavirus pandemic is leading to losses in GDP and developing countries are taking on increasingly more debt to pay for their responses to the crisis. In this context debt relief is looking increasingly important with groups such as the Economic Commission for Africa calling for support to tackle the growing debt burdens.

The OECD-DAC foresees debt relief through ODA as a solution to this growing crisis. They argue that if debt relief were not counted as ODA, countries with scarce resources might lend more rather than providing relief on existing debts. However, not everyone agrees with this. The European network on debt and Development, Eurodad, argues that such incentives are redundant since most debt relief is given out of necessity, when highly indebted low-income countries can no longer pay and face debt defaults. They also argue that ODA rules should incentivise grants over loans, to help prevent countries falling into unsustainable debt in the first place.

Debt relief is defined as both debt forgiveness, either in part or in full, as well as debt restructuring. The move has implications for levels of ODA spending. Many countries have annual ODA spending targets, with some reaching the international standard of 0.7% of gross national income (GNI). Under the new rule debt relief may displace other aid flows as countries look for new ways to reach their ODA spending targets in the context of recession and unemployment at home.

Responding to concerns over unsustainable lending, the World Bank earlier this year implemented a one year debt moratorium and called for greater transparency of public and private debt terms in order to ensure they work for developing countries. But what does this mean for the transparency of international aid more generally?

What do we currently know about debt and debt relief?

Although donors record ODA loans to developing countries in their OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) reporting statistics, as well as in the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) Standard, other official lending and credit arrangements, such as through Export Credit Agencies, are more opaque. Even when these debts are forgiven and recorded as ODA, they generally remain shrouded in secrecy, avoiding accountability and inhibiting learning from unsustainable lending practices.

In the worst cases, outstanding debts may be of questionable legitimacy. For example, in 2012 it was discovered, following an FOI request, that UK Export Finance, the UK’s Export Credit Agency, had large historic sovereign debts for military equipment sold to dictatorships in Egypt, Argentina and Iraq. While relief of such odious debts would be welcome, there is a strong moral case that these should simply be written off, and that such write offs should not count towards countries’ ODA obligations.

The data on debt relief and the data gaps

To gauge current transparency levels of debt relief Publish What You Fund researched the information available through the two main international data sources – the OECD DAC CRS and the IATI registry. Some debt relief is already being recorded as ODA flows in the OECD DAC CRS – the 2018 CRS figures show a total of USD 755 million of debt forgiveness or restructuring by governments. Among these the largest bilateral creditors to provide debt relief were: Russia (agency name not given), France’s Ministry of Economy, Finance and Industry and Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The UK recorded a USD 4.7 million cancellation of debt owed by Cuba to the aforementioned UK Export Finance (then known as UK Export Credit Guarantee Department).

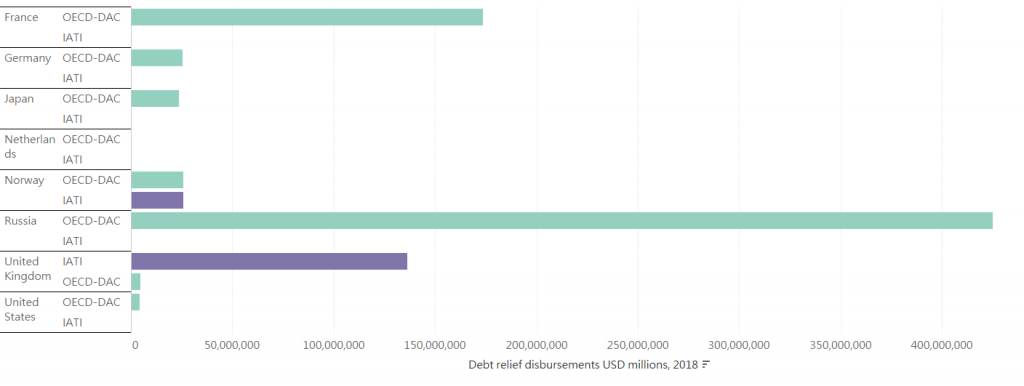

We wanted to delve a bit deeper to find out what the loans were originally made for and under what terms the debt relief was made. Since the CRS data only provides basic project information, we took our search to the IATI registry instead. Surprisingly, a search for debt relief under both aid and finance type revealed only USD 162 million of disbursements in 2018 across just eleven IATI activities. This is around 20% of the amount reported to the OECD-DAC CRS. The graph below compares the published figures of debt relief across the two data sources. Norway was the only donor country that matched in its reporting across both data sources. Many countries including France, Germany and the US reported no debt relief disbursements in 2018 to the IATI registry. This represents a significant data gap.

For countries that do report their debt relief to the IATI registry, details of the debt relief terms as well as information about what the original loans were for were not available in any cases. For example, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), one of the highest scoring bilateral donors in Publish What You Fund’s 2020 Aid Transparency Index, had two published debt relief activities in their 2018 IATI data. Neither of these provided information beyond disbursement amounts, dates and the agency name where the debt relief was paid. This means we do not even know which developing countries the debt relief benefited. It appears that the only data available on debt relief in the IATI registry are country contributions to the 2005 Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). This is an IMF initiative to cancel the debts of multilateral creditors. We could find no bilateral debt relief being reported through IATI.

So, as well as finding no information about the original loan or terms of the debt relief, we were also not able to find much of the information which is generally made available for traditional ODA expenditure in the IATI Standard. This includes basic project attributes such as benefitting sectors and activity descriptions. For debt swap initiatives—which forgo debt repayment on the condition that the funds are channelled to specific social projects—there was also no performance related data available, such as the objectives and results or evaluations, which would be needed to assess the impact of these programmes.

Transparency standards on debt relief should be raised

It seems that detailed information on bilateral debt relief is not readily available in either the IATI or OECD DAC CRS data. With the likelihood of more debt relief being granted as ODA as countries struggle with their debts in the wake of the COVID crisis, transparency standards should be raised. The specific characteristics of ODA—public money provided to promote the economic development and welfare of poor populations around the world—confers additional transparency and accountability responsibilities on donors. As aid and debt become increasingly intertwined, transparency of both will be needed to provide a complete picture of how taxpayers’ money is used in developing countries and what impacts this has on poverty and development.

This is not an area which has typically been a focus for the aid transparency movement so there is a lot of new ground to cover. What are the transparency implications if increasing amounts of ODA are to be spent on relieving opaque debts, with little information available to the public about the arrangements or benefits? What guidance should IATI provide for publishers? How can the large reporting gap be improved? Should a new public registry be created with full details and terms of loans and credits to developing countries, or could this data be incorporated into existing transparency platforms? These are some of the questions we will be asking going forward.

Related posts:

Who funds women’s economic empowerment – a data journey

Donor financing for gender equality: spending with confusing receipts