Reflections on the Development Finance Debate: Putting Principles into Practice

The debate on the role of private finance in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is intense and lively. The need for transparency comes up again and again. But how do we move from debate to action?

We know that development finance institutions (DFIs) are playing a more significant role in financing efforts towards the achievements of the SDGs, regardless of whether this is through ODA investments, use of ODA as subsidies, or just through the investment of public money in projects with a developmental outcome. To put this into scale, in 2014 the annual total commitments of DFIs equated to $70 billion, and this was before the increased investment in CDC in the UK[1] and the creation/recapitalisation of new DFIs in the US, Australia, Canada and China.[2]

We also know that transparency should be a norm by now; it has been enshrined in the under-pinning policies pertaining to DFI operations for years, including in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in 2015. Since then, as the focus on blended finance has increased, transparency has been presented as a core pillar of the DFI working group’s Enhanced Principles on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects through to the OECD’s Blended Finance Principles (principle 5) and now the 2018 Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance.

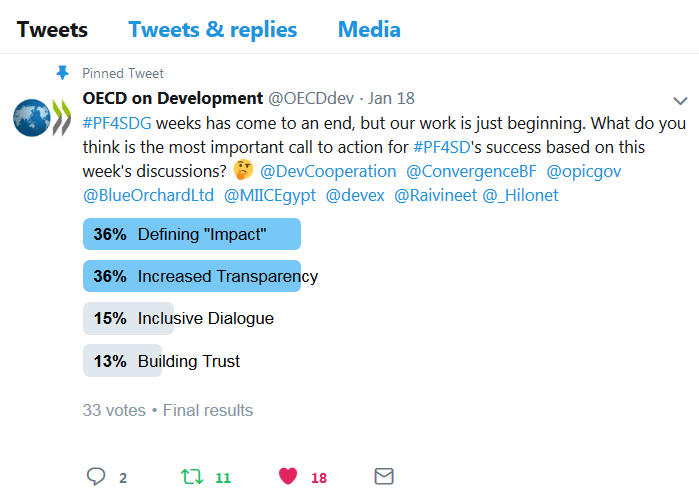

Two weeks ago we met with a broad array of experts, researchers and of course representatives from private banks and DFIs at the OECD’s Private Finance for Sustainable Development (PF4SD) conference in Paris. The OECD once again highlighted the urgency of the transparency issue when it launched its latest report, “Social Impact Investment 2019: The Impact Imperative for Sustainable Development”. Under its data pillar, the report clearly calls out the need to “facilitate transparent, standardised and interoperable data sharing – requiring coordinated efforts in the development and implementation of data standards as well as linkages between existing data platforms”. And if we ever needed more proof, what could be more methodologically sound as a means of highlighting the importance of transparency than the OECD’s own Twitter survey held after the conference?

The question now is to what extent these intentions are being translated into action; how do we put these into practice?

One example of progress relates to the work being undertaken at the IFC on their Anticipatory Impact Measuring and Monitoring (AIMM) system. Presented at the OECD conference and soon to be launched in the spring, the AIMM system enables IFC to “estimate the expected development impact of their projects—at their initial stage, when they are still being developed”. Based on the criteria the IFC has already made public, the system allows for detailed, sector-specific pre-investment analysis of potential developmental impact as well as the impact on market creation. From a transparency perspective, the AIMM system is very welcome. Once the detail of the scoring methodology is shared publicly stakeholders will be able to much better understand the process and rationale behind IFC’s investments – a big step on the path to accountability.

However, with impact measurement and transparency being so high on the agenda, a number of questions remain for the IFC as it implements the AIMM system. To what extent is it the intention that ex-ante AIMM scores for individual investments will be shared? Will there be mid-line or ex-post evaluations against those same AIMM scores to determine progress or as a proxy for impact? Will these be made public?

The AIMM system is one leading example of work by DFIs to move forward on measurement. While we appreciate that sharing impact information is uniquely challenging for DFIs because of confidentiality and market sensitivity reasons, the discussions at the PF4SD conference underscored the need for academically rigorous, harmonised and transparent approaches to impact measurement. If these new metrics, and the data arising from them, are not shared publicly, then a huge opportunity for improved learning, better coordination and ultimately improved impact will be lost.

[1] The decision to invest further in CDC was taken after the passing of an Act of Parliament in February which received cross-party support and raised the limit of the level of financial support that can be provided to CDC from £1.5bn – a figure set 18 years ago- to a maximum of £6bn.

[2] See ODI/CSIS report “Development Finance Institutions Come of Age”, October 2016, by Runde, D., Willem te Velde, D., Savoy, C., Carter, P., and Lemma, A.