Chinese Aid – Competition or Colonialism?

China has repeatedly come under fire for its aid and development practices. “Negative impact”, “roll[ing] back transparency” and “unsustainable debt” are some of the terms used to describe Chinese foreign assistance by Jim Richardson, coordinator of USAID’s Transformation Task Team. He is not alone in his criticism. Ray Washbourne, President and CEO of OPIC, suggested that China is over-building and over-loaning, saddling developing nations with unnecessary debt. The Australian International Development Minister, Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, recently caused a diplomatic spat by saying much the same. However, perhaps it was the Malaysian Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad, who has been the most blunt in his appraisal: “a new version of colonialism”.

So is this fair? The answer is not so simple.

Chinese aid is most certainly opaque. The country has repeatedly come last in our Aid Transparency Index and tracking what and where it is operating is notoriously difficult. In fact, as part of our project to assess the impact of the deep cuts proposed by the US Administration in four countries, we found ourselves trying to decipher Chinese assistance. Quite simply, we needed to landscape which donors were doing what so we could determine what gap might be left if the US slashed its assistance or withdrew. This wasn’t easy. When asked whether we could learn what China was doing in Liberia — one of our case-study countries — an interviewee remarked “it would be easier to uncover State secrets.”

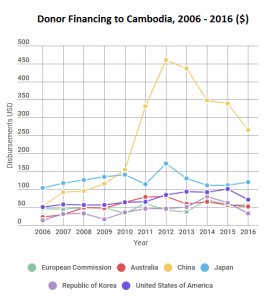

Things were a little different in Cambodia, another of our case-studies. Fortunately, in Cambodia we were able to use government aid management data. Details were still sparse but we had enough to identify the extent and growth of Chinese assistance to the country.

In 2006, China’s assistance to Cambodia was roughly equal to that of the United States at $53.2 million. At its peak in 2012, it accounted for $460.7 million while Cambodia’s next largest donor, Japan, disbursed $172.3 million. Despite a gradual decline — reportedly due to government nervousness of mounting debt — China still accounted for $265.3 million as of 2016. That is equivalent to one fifth of all aid disbursed to the country that year.

Chinese projects are typically large infrastructure projects, funded through low interest “concessional loans” that need to be repaid. Although that is still largely the case, our research uncovered a small grant program, with China providing $9.2m of grants to Cambodia in 2017, up from zero in 2014.

Perceptions of Chinese assistance are divided. On one hand, senior officials we spoke to in the Cambodian government clearly favoured it. Moreover one such official welcomed the “competition” it brought to the development sector and claimed: “Chinese loans come with less strings [than Western loans], the government can set the priorities, the interest rate is cheaper, terms are better and we can procure it faster”. While still complimentary of other donors, he lamented the continual donor pressure for human rights and democratic governance reforms and considered these issues “over-addressed”. In all, he concluded “from a competitive point of view, we will obviously take Chinese loans”.

Others were less favourable. Numerous civil society representatives expressed concerns that Chinese assistance was not only less transparent but it had no policy to engage or consult with civil society. A Cambodian watchdog organisation, for example, suggested that because the Chinese government sees itself as a partner of the Cambodian government rather than a donor, it does not feel responsible for meeting the same obligations towards transparency, coordination and civil engagement.“If USAID doesn’t explain itself I will ask for a meeting at the Embassy… But China is hard to talk to, and if there’s no policy [to meet with civil society] how can we ever engage?” he said.

Others expressed greater anxiety about what China seemed willing to fund, rather than what it was doing. Several interviewees suggested that Chinese funding is now flowing through the recently formed and Cambodian government-backed Civil Society Alliance Forum. This Forum, which openly competes with independent civil society forums, provides small grants for rural development NGOs. These funds, however, come with political strings attached. Recipients are not permitted to challenge government policy and would ideally align with the ruling party. This comes during a time of an openly authoritarian crackdown on Cambodian political opposition by the government there.

In all, much remains murky about how and where China is investing its development finances. We did not focus on China’s assistance in our US Foreign Assistance project and much work would be needed to truly answer the question put forward at the beginning of this blog. We did, however, learn that their growing role has not only disrupted the traditional donor landscape but opened up serious challenges for those seeking to embed transparency as a development norm while ensuring that international cooperation is more accountable and inclusive to local actors.