Aid transparency: a focus on major donors in Kenya

This week, global leaders and major development cooperation stakeholders gathered in Nairobi for the second high-level meeting (HLM) of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC), hosted by the government of Kenya.

The meeting has a number of objectives, among which is to take stock of the development effectiveness principles – ownership, partnership, focus on results, and transparency – set out in the Busan Partnership Agreement. It was in 2011 at Busan that major donors committed to provide timely, comprehensive, and comparable data on their development activities in an open standard.

The Kenyan government and international partners have been involved in development cooperation partnerships for a number of years. Kenya’s hosting of the HLM this year demonstrates its strong leadership in engaging with all partners. In its Vision 2030 strategy, the Kenyan government has set an ambitious agenda to achieve middle income country status by 2030.

So, before new commitments are made, how have major donors fared on their transparency commitments and what are the implications for a country like Kenya?

The importance of development support to Kenya

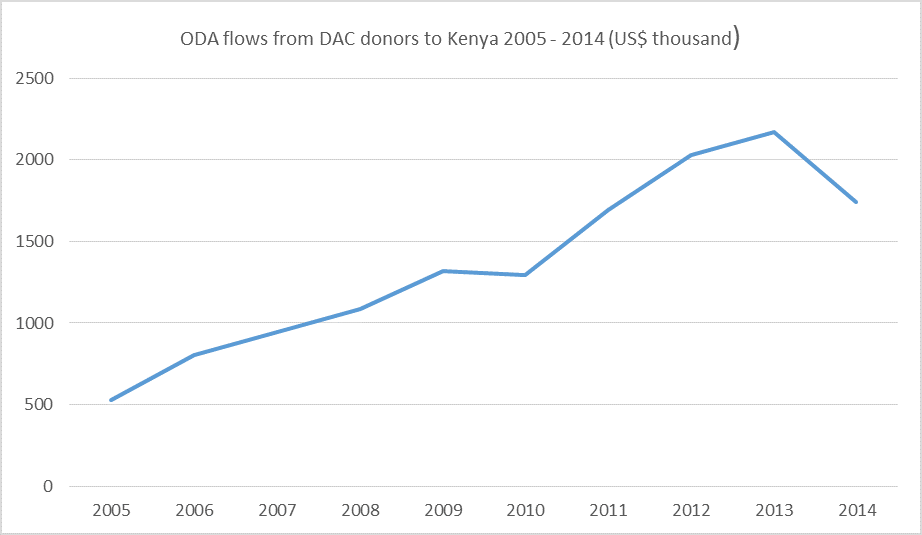

Source: OECD QWIDS

In 2014, Kenya received US$17.40 million ODA according to OECD DAC CRS figures. Flows to Kenya had been rising incrementally since 2005 but had tailed off in 2014. Data published to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) – which allows for current and forward looking data on development projects to be published – for 2015, suggests a recovery in the growth of these flows.[1]

Sectors

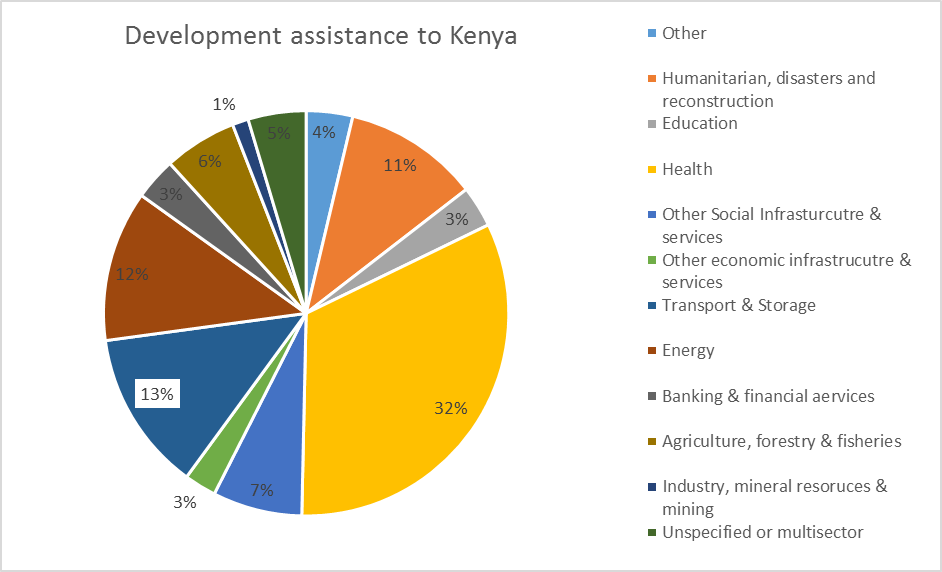

Source: 2014 OECD DAC CRS

In 2014, health was the largest sector into which development assistance flowed, accounting for 33% of flows and constituting approximately US$1 billion. Transport and humanitarian aid were two other key areas of development assistance to Kenya.

Major donors

It is unsurprising to see the major donors to Kenya also figure among the leading donors worldwide. Based on 2014 OECD DAC CRS data, the combined agencies of the United States account for just twenty-five percent of Official Development Finance (ODF) to Kenya. The World Bank’s International Development Association accounts for a further eighteen percent of flows. Other major donors are the African Development Bank, the European Union institutions, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Japan. Not captured in CRS statistics but clearly a major partner to Kenya is China, whose budget is estimated to be roughly US$295 million a year.[2]

Data gaps and unfinished business

Since 2011, Publish What You Fund has been monitoring the performance of major aid providers in making their aid transparent with the Aid Transparency Index. The last report demonstrated that while more and better data on development activities has been made available in the past few years, key players and key pieces of information on projects are still missing. Data available on development activities in Kenya is no exception to this.

Data on individual activities published on the IATI Registry combined with the results of the Aid Transparency Index show where gaps remain:

- Some major donors such as Japan MOFA have very poor levels of transparency, yet its disbursements in Kenya are not marginal, standing at US$24.9 million. China makes almost no disaggregated data available on its activities.

- More activity-level data on individual activities, particularly relating to performance is needed from all key donors. Generally, only limited data is made available on objectives, impact appraisals, evaluations, and results.[3]Japan, the EU and Germany for example do not publish results to the IATI Registry.

- Disaggregated budgetary data of these donor organisations is also in short supply.

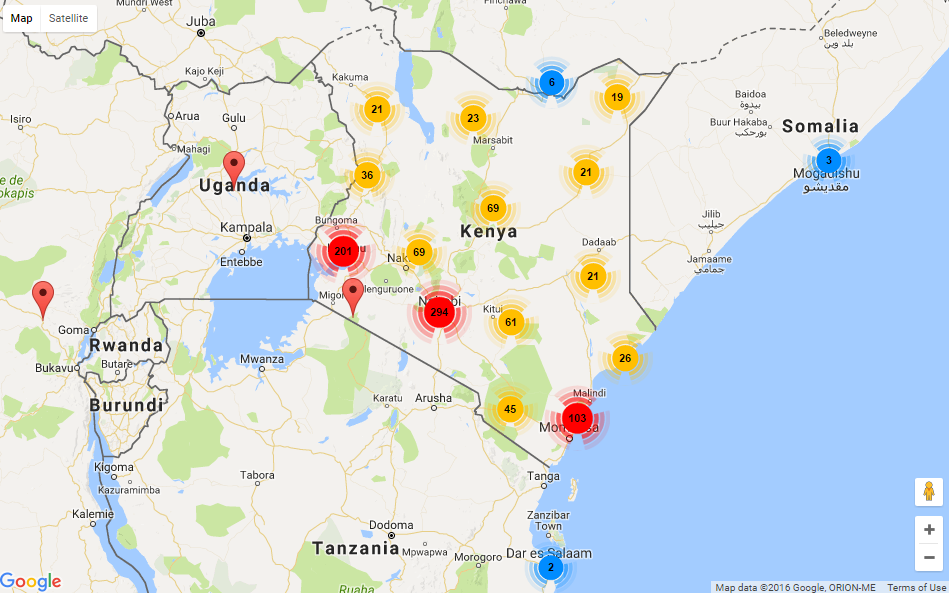

- Finally, more subnational location data is also needed. On D-portal, just 9% of activities published to the IATI Registry have geocoded sub-national locations attached and most appear to be concentrated in urban areas. Only three projects are located in Dadaab, one of the world’s biggest refugee camps.

What next?

Earlier this month and ahead of the HLM meeting, the government of Kenya launched its Kenyan External Resources Policy (KERP), a framework for management of overseas aid into the country.[4] The policy should provide a clear path to more effectiveness, efficiency and impact of external resources provided by both donors and non-state actors to support the government’s aid exit strategy.

This policy, coordinated by the Kenyan Government, is a repeated call for all stakeholders participating at the HLM to commit and deliver on their promises by sharing more and better data on their activities. It is also an opportunity to demonstrate the usability of the data published for planning and monitoring purposes.

The initiative will only be successful if done in collaboration with existing donors who should build on their efforts from the past few years and complete the unfinished business before making new commitments. That involves providing more updated and disaggregated data on the areas highlighted above and publish these to the IATI Registry to support the Kenyan government’s efforts. Kenyan authorities as well, both at federal and county levels, are required to publish budgetary information at multiple stages of the budget cycle.[5]

This exercise should also involve emerging or new partners, including those from the private sector. Historically, these actors have been subject to less scrutiny. The need for more and alternative sources of finance in Kenya and worldwide for the years to come will mean that they might have a bigger role to play. For example, Kenya’s flagship project, the LAPSSET Corridor Program, is set to be East Africa’s largest and most ambitious infrastructure project designed to foster trade, economic linkages and interconnectivity in the region. But concerns have also been raised on overall costs and social and environmental impacts of some of these projects might have on local communities.[6] Data provided by all stakeholders, private and public ones, should help monitor the transformative impact that such a project could have on the country and the region while mitigating the risks.

Finally, these transparency efforts should lead to closer engagement with civil society organisations and citizens. Kenya is organising its next round of elections in August 2017. The provision of more data on development activities by all partners supports active citizens willing to be kept informed on key issues.

[1] https://app.iatistudio.com/app/chartbuilder/583871cd1365c93208341214

[2] See Dollar D., ‘China’s engagement with Africa’, Brookings Paper, 2016; Prizzon and Hart, ‘Kenya in the new development finance landscape’, ODI report, April 2016.

[3] See 2016 Aid Transparency Index results http://ati.publishwhatyoufund.org/index-2016/results/, and further analysis on results information https://www.publishwhatyoufund.org/updates/by-topic/iati/open-results-information-what-do-we-know/

[4] See: http://www.treasury.go.ke/media-centre/news-updates/402-launch-of-the-kenya-external-resources-policy.html

[5] See IBP’s work on budget transparency in Kenya: http://www.internationalbudget.org/budget-work-by-country/ibps-work-in-countries/kenya/understanding-county-budgets/tracking-county-budget-information-kenya/

[6] See more on The Mipakani Project is an open-access knowledge base covering the Lamu-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor http://www.mipakani.net/ ; or the Rift Valley Institute briefs: http://riftvalley.net/publication/lapsset-transformative-project-or-pipe-dream#.WD2P7vmLSUk