Developing a Homegrown Aid Database: Lessons from Bangladesh

This is a guest blog post by Mehdi Musharraf Bhuiyan of the Aid Effectiveness Unit, Economic Relations Division, Government of Bangladesh.

“It is satisfying to note that the response from our development partners since the establishment of AIMS is very encouraging. For the majority of donors on the system, we now have a quite comprehensive data set. It is expected that regular and timely data sharing on AIMS will ensure better availability of comprehensive, accurate and timely aid data to get a complete picture of aid flows. This will improve national budgeting and promote sector level alignment with national priorities spelled out in the 6th Five Year Plan”– said Mr. Mohammad Mejbahuddin, Senior Secretary of Economic Relations Division (ERD) of the Government of Bangladesh and Vice Chair of IATI in a newspaper article.

Foreign aid still plays a significant role in the overall development of Bangladesh. Up-to-date information on aid flows, however is often only available off line. It is also currently scattered between different institutions in charge of aid coordination (Economic Relations Division (ERD)), development planning (Planning Ministry), monitoring results (IMED), and project negotiation with donors (Line Ministries).

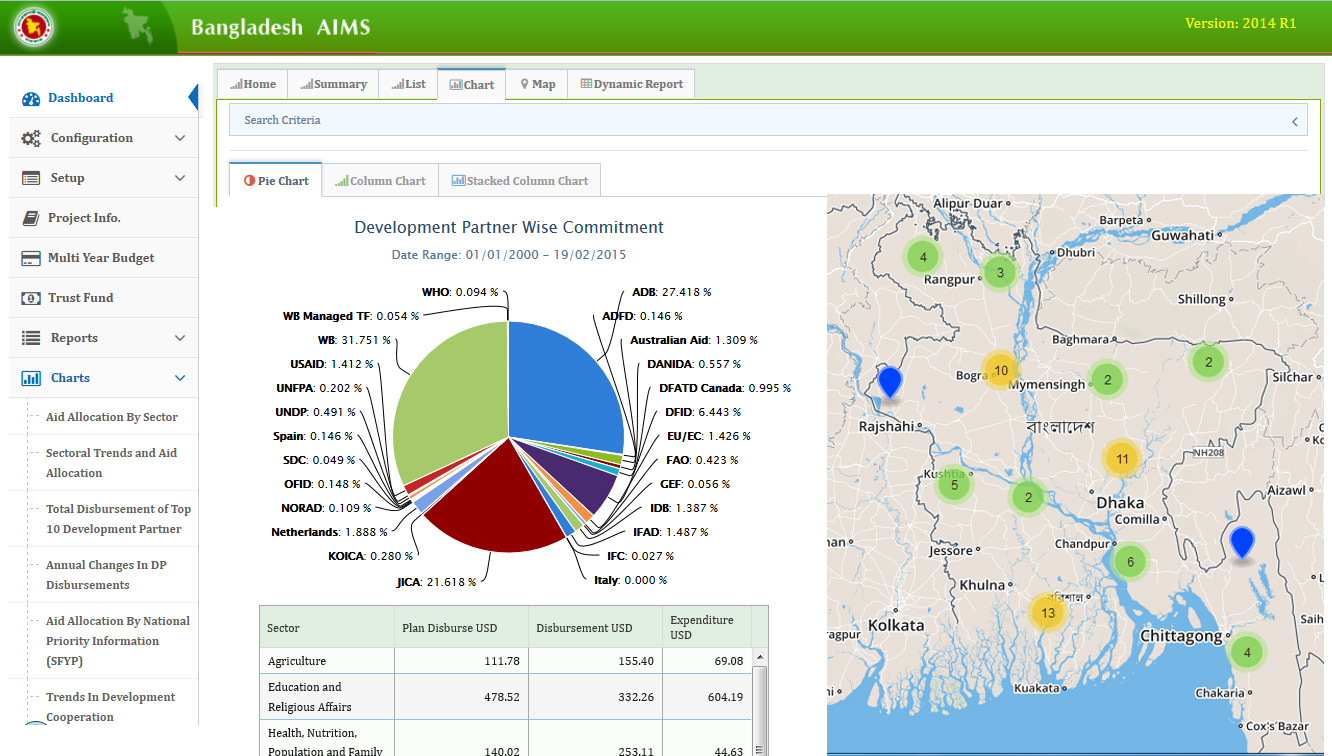

To provide a single point for all foreign aid information and to properly track and manage aid flows in Bangladesh, the ERD, with support from the Aid Effectiveness Project, has developed a homegrown Aid Information Management System (AIMS). The AIMS covers all sectors, projects and donors and offers a single software application that records and processes information on development activities and related aid flows.

Donors have to register to enter their data into the AIMS. So far, 17 out of around 28 agencies working in Bangladesh have registered and it is expected that the remainder will do so soon. For the donors who have not registered, their aid data continues to be captured by offline outreach through Excel sheets that only documents commitments and disbursements.

One key thing we have found is that we were initially confronted with limited awareness among donors around their international commitments in the field of aid transparency, little understanding of IATI standards and a lack of willingness for donors to provide project data to the AIMS. However, extensive consultation and training has been undertaken to address this issue and will continue to take place, which has already resulted in an increase of data uploaded.

The data on our aims is currently provided directly by the donors, but we are in close touch with the IATI Secretariat and we will be piloting automatic data collection from the IATI Registry soon. There are certain limitations of automated transfer of IATI data which, do still need to be addressed. These include:

- Multi—donor projects, when drawn from the IATI data-store, gets reflected in AIMS as multiple projects.

- Funds that are channeled through multilateral agencies cannot be traced back to their original donor within IATI.

- Experience of the IATI secretariat also shows that considerable manual verification by the local donor office is required for the static- or non-financial- data due to generally poor quality of the data published in the IATI registry.

- Very few donors publish forward looking data into IATI. This means that forward looking data would still have to be entered manually by the local DP office.

So, what have we learned that might be of use to others thinking of developing a homegrown aid database?

- The Bangladesh AIMS was developed through a wide consultative and inclusive process involving the government, development partners and civil society organizations over a period of 20 months. This ensured that the design was adjusted to the needs of future users and local stakeholders. For example, a key ask was that the system is interoperable with other Government databases.

- The design went through several stages of evaluation before it was made fully accessible. It went through prototyping and user testing to a BETA version that was released, with limited accessibility, for online testing. This step-by-step process allowed us to fine-tune the design, including adding a number of additional data fields and reporting features and addressing interface issues in the later stages of development.

- By opting for a home grown, locally developed software, we ensured that the design cost was much lower and there are no continuous licensing fees. Key cost saving points are:

- The source code and software documentation will be available to the Government, which allows further customization at minimum cost.

- Server costs are kept at local market rates.

- Upgrading the system need only be done when the Government (not the service provider) requires them.

- The maintenance cost of the AIMS can easily be absorbed in the revenue budget after project closure.

- The system is interoperable – e.g. it can be integrated with other Government databases such as domestic budgets (iBAS), debt management (DMFAS) and the upcoming M&E database.

- In Bangladesh, the use of up to date digital equipment (e.g. – tablets and smart phones) in public institutions and civil society organizations is still limited. Government institutions, in particular, are still in the process of switching from paper-based to digitized systems. Taking this into account, the AIMS application has been customized for easy use on traditional ICT tools like desktop PCs and laptops. This can be an important lesson for countries that are still lagging behind in terms of ICT usage.