What’s next for U.S. Government aid transparency? Data quality for data use

This is a guest post by Josh Powell, Director of Innovation at Development Gateway

Earlier this month, Publish What You Fund’s U.S. Aid Transparency Review showed strong improvements from the U.S. Government (USG). In particular, USAID should be congratulated for its leap from a narrowly achieved “Fair” to a solid “Good,” while MCC continues to be a global leader in aid transparency with a “Very Good” ranking in this year’s index. Both USAID’s and MCC’s ratings indicate that they are “on track” for their Busan commitments on transparency, while other USG actors remain sluggish and “off track.”

In typical form, InterAction’s Laia Grino does a better job explaining USAID progress than I can (I encourage you to read her piece here). Among other advances, USAID’s IATI Cost Management Plan (CMP) has deservedly gained plaudits as a practical strategy to deliver on its transparency commitments. In addition to plans for expanded field coverage in USAID reporting, the CMP calls for the creation of a dedicated working group on data quality. I would suggest that the post-haste creation and execution of this working group is the single most important next step for USAID, and one which other USG agencies would do well to emulate.

As Laia put it, “bluntly: the current quality of USAID’s data makes it largely unusable.” Our experience suggests that, at least for partner country governments, this is indeed the case (and it should be noted that USAID is not alone, among USG or beyond). For example, under our current effort to use IATI data in country systems, we have been unable to include any USG agency among the pilot list of leading IATI publishers whose data will be automatically imported into government-owned aid information management systems in Burkina Faso, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Madagascar, and Senegal. This decision to omit USG data was driven far more by the overall quality of data reported by the U.S. than by the omission of any specific fields. In practice, country government users care most about a core set of less than 20 fields, suggesting that USG would be best served by placing its investment in improved quality than expanded coverage.

Let’s use the case of Senegal to illustrate a few examples of the challenges a government official or CSO staff would have with using USG data:

1) Sector codes are missing from USG data 20% of the time in Senegal. When specified, they are provided in USG Sector Vocabularies, rather than local or OECD DAC sector codes. Requiring local users to convert USG sector codes into meaningful classifications for their context creates a high barrier to effective local use. A look at the IATI data quality dashboard shows that, across the board, USG uses an inconsistent mix of its own and OECD sector classifications.

2) Planned Start and End Date fields are missing from USG data for 88% of activities in Senegal, and Actual Start and End Date fields are missing 32% of the time. These dates represent key fields for users to understand which activities are active, and when activity outputs should be completed.

3) All data are reported in English only, severely limiting the usefulness for a Francophone country like Senegal. Fortunately, the CMP highlights local language publication of activity titles and descriptions in local languages, but USG should go a step further and publish sector codes, transaction types, and other key fields in the local language as well.

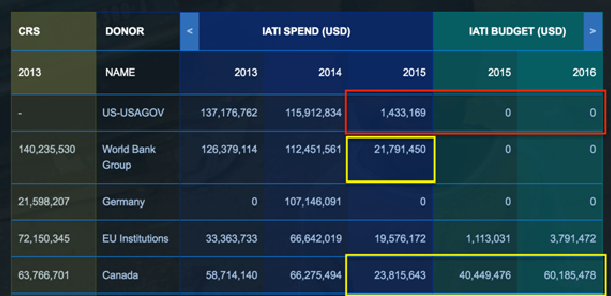

4) Up-to-date data are perhaps the most critical element for partner country use. A quick glance at D-Portal for Senegal shows that, as of July 19, only $1,433,169 in disbursements have been reported in 2015 – compare this with $115,912,834 in 2014, and World Bank reporting of $21,791,450 thus far in 2015. Furthermore, no budget data for 2015 or 2016 are available (compare this with Canada, which reports projected budgets for 2015 and 2016). We cannot continue to expect IATI users to make today’s decisions with last year’s data.

Without improvements to the quality of the data reported by USG (and nearly all other IATI publishers), it will make little difference what quantity of data is ultimately published. As our colleagues within USG look forward, let’s focus less on transparency, and more on effective transparency; less on publishing more information, in favor of publishing more useful information; less on meeting commitments, but more on meeting challenges to using open data to improve outcomes.